Holotopia: Narrow frame

Contents

H O L O T O P I A: F I V E I N S I G H T S

Narrow frame

Science gave us a completely new way to look at the world. It gave us powers that the people in Galilei's time couldn't dream of. What might be the theme of the next revolution of this kind?

Science was developed as a way to find causal explanations of natural phenomena. Consequently, it has served us well for some purposes (such as developing science and technology) and poorly for others (such as developing culture).

But its main disadvantage in the role of 'headlights' is that it constitutes a 'hammer'; it coerces the creative elite to look for the 'nail'—and ignore the needs of the people and the society.

Stories

This is not an argument against science.

Science has served us excellently in the role it was created for. There is no reason to believe that it will not continue to do so.

Our theme here is how we create truth (what we collectively believe in) and meaning, about the matters of which our daily life and interests are composed. And also those other matters, which demand our attention but remain ignored.

We have an urgent need for orientation and guidance.

In all walks of life—so that we may see things as we need to see them; and direct our efforts productively and wisely.

Our point of departure is the fact that nobody really thought about and created the way we create truth and meaning about the themes that matter. What we have, and use, is a patchwork made out of fragments from the 19th century science (which were there when our trust in tradition failed, and our trust in science prevailed), and popular myths. We tend to take it for granted, for instance, that something is trustworthy, true, legitimate or real, (only) if it is "scientifically proven".

Our point is that we can do better.

And that our task at hand (federating Aurelio Peccei's call to action, to pursue "a great cultural revival") requires that.

We must return to reason

Stephen Toulmin's book "Return to Reason" provides a historical view of our theme, from the pen of a prominent philosopher of science. Toulmin's point is that for historical reasons, academic research got caught up in a disciplinary pattern deriving from the 19th century physics—which obstructs and confines academic creativity. Toulmin's call to action is to "return to reason"—and apply it creatively and freely (see our summary).

Insights from physics

In "Physics and Philosophy" (subtitled "Revolution in Modern Science"), Werner Heisenberg observed that the way of looking at the world that our general culture adopted from the 19th century physics constituted a "rigid and narrow frame", which was damaging to culture. Heisenberg explained why the results in contemporary physics amounted to a scientific disproof of the narrow frame (see our summary here).

Heisenberg foresaw that the epistemological insights reached in modern physics would naturally lead to cultural revival. Click here to hear Heisenberg say that

Most people believe that the atomic technique is the most important consequence. It was different for me. I believed that the philosophical consequences from atomic physics will make a bigger change than the technical consequences in the long run. (...) So we know because of atomic physics and what was learned from it that general problems look different than before. For example, the relationship between science and religion, and more generally, the way we see the world.

Insights from the humanities

In the humanities, it is common knowledge that the ways of looking at the world we have inherited from the past will not serve us in this time of change. See our comments that begin here.

Insights from philosophy

Wittgenstein observed that words and expressions acquire their meanings only as parts of specific familiar situations, or language-games. His arguments suggest the conclusion that we cannot really use language to "change the game", which is our task at hand (see our comments here; take a look at the reflection that follows, about Robert Oppenheimer's "Uncommon Sense", where it is indicated why not only our language, but also our "common sense" might be a hindrance).

So far we have been repeating what everyone knows—that the way we see the world and make sense of the world is determined by our cultural paradigm. So can we at all liberate ourselves from this entrapment, and communicate in a way that changes the paradigm?

Einstein will give us a clue.

Insights from Einstein

Knowledge can grow 'upward'

Einstein's "Autobiographical Notes" is, roughly, Einstein's equivalent of Heisenberg's just mentioned book—where Einstein looks back at the whole experience of modern physics, and draws conclusions. Einstein first lists all the successes that were derived directly from Newton's approach, then the "anomalies"—phenomena that could not be handled in that way. Then he offers a somewhat dramatic conclusion, as shown above.

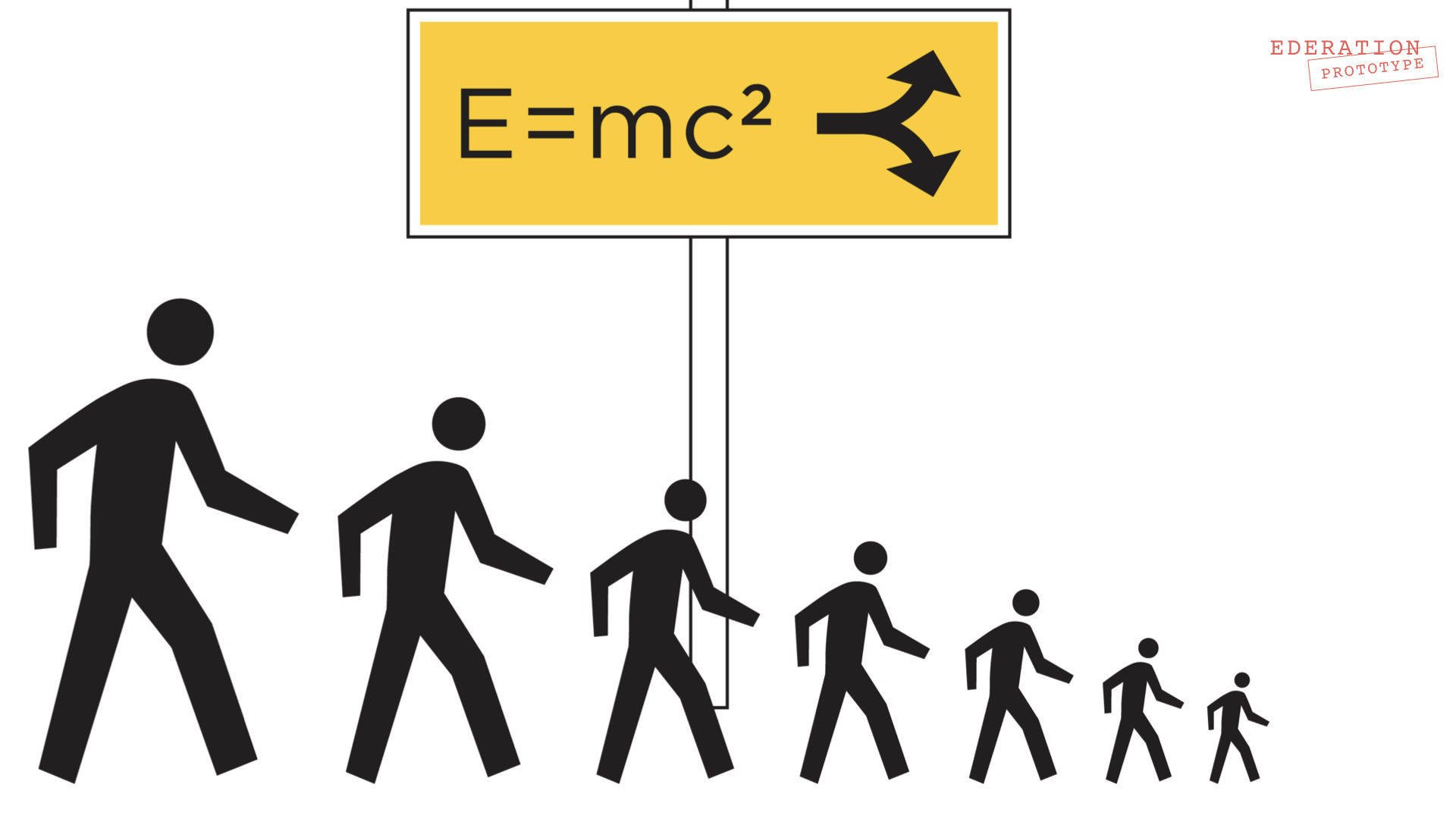

Science on a Crossroads ideogram

Science on a Crossroads ideogram

We condense the whole thing to the above ideogram (an alternative to the one given below?). The moment Einstein was describing was that Newton created a method and a set of concepts, which offered only an approximation of "physical reality"—which was good enough for a couple of centuries of progress, but not any longer. Immediately, Einstein explains that they will have to be replaced (by physicists, of course) by ones "further removed from ...", i.e. ones that are more technical and less intuitive. Science, following its own course, continued to evolve 'downwards'.

But a completely different direction at that point also became possible: To do what Newton did in all walks of life! Create concepts and methods that work approximately, but well enough...

The method we are proposing builds on Einstein's "epistemological credo", given in Autobiographical notes (which we commented on here).

I shall not hesitate to state here in a few sentences my epistemological credo. I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions that are laid down in books. (…) The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system. (…) All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits, just as is the concept of causality, which was the point of departure for this inquiry in the first place.

To be continued