IMAGES

Contents

- 1 Federation through Images

- 1.1 Reimaging the Enlightenment

- 1.2 These images are ideograms

- 1.3 Invitation to academic self-reflection

- 1.4 Reflection

- 1.5 We can go through!

- 1.6 We can liberate knowledge

- 1.7 Growing knowledge upward

- 1.8 Redirecting knowledge work

- 1.9 Knowledge federation in two pictures

- 1.10 Two examples

- 1.11 Reflection

Federation through Images

Reimaging the Enlightenment

Enlightening the everyday

Can our society's capability to comprehend be enhanced in the degree that marked the Enlightenment?

Can we experience a similar dispelling of prejudices and illusions – in our understanding of love, happiness, religion, social justice and democracy?

In these detailed pages of our presentation we provide food for this line of thought.

In the first story of Federation through Stories we show how the developments in modern physics, and in science and philosophy at large, disrupted our notions of what knowledge and pursuit of knowledge are about. The notions that the 19th century science gave our popular culture, which still persist.

The giants of modern science saw that what they were discovering was not only the behavior of small quanta of matter, or the social mechanisms by which the idea of reality is constructed, or the neurological mechanisms that govern awareness – but that the bare foundations of our creation of truth and meaning were emerging from the ground.

Having thus lost its innocence, its "objective observer" self-image, science acquired a new capability – to self-reflect. And through self-reflection to understand the limitations of its own approach to knowledge.

Here, in Federation through Images, we shall depict the academic and human situation that resulted – and propose how to continue.

We shall see why what we've learned, and the situation we are in, empower us to extend the extent of scientific knowledge to any theme that matters.

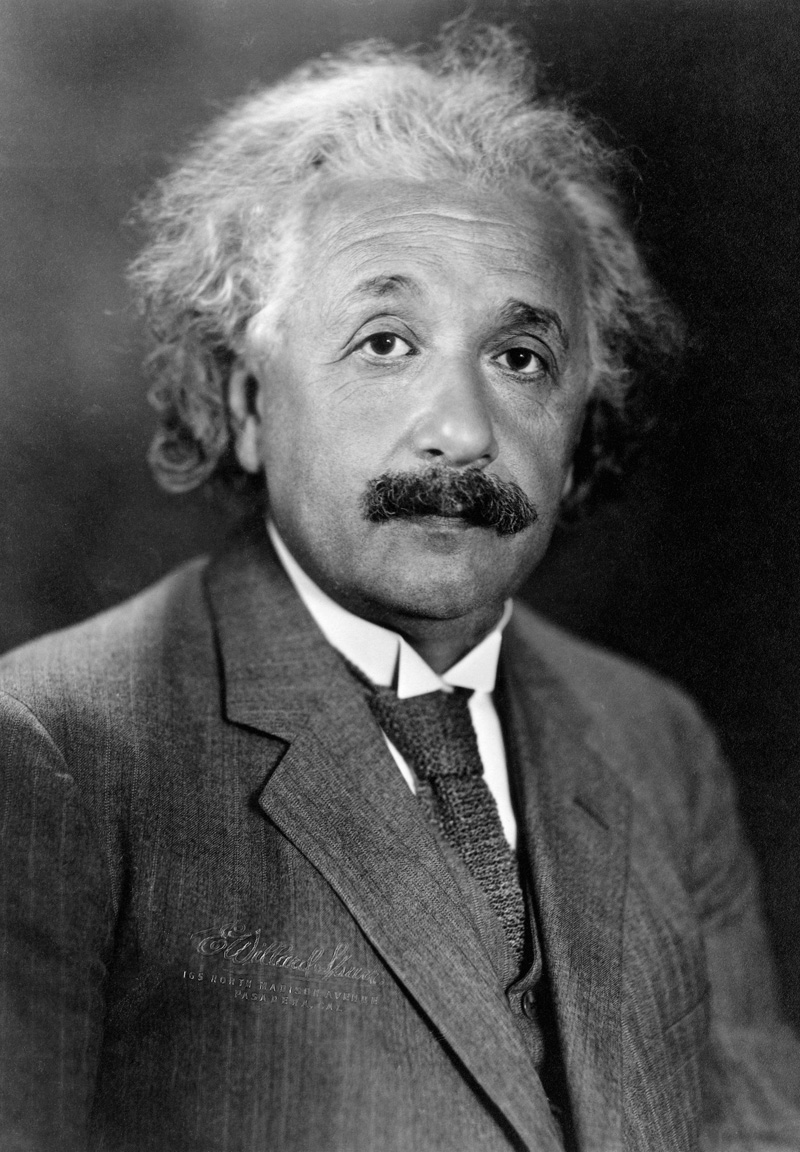

Our giant in residence

While we build on ideas of a whole generation of giants, in this condensed presentation they will all be represented by a single one – Albert Einstein. Einstein will here appear in his usual role, as a modern science icon.In spite of all the fruitfulness on particulars, dogmatic rigidity prevailed on the matter of principles: In the beginning (if there was such a thing), God created Newton's laws of motion together with the necessary masses and forces. This is all; everything beyond this follows from the development of appropriate mathematical methods by means of deduction.

The just quoted lines from Einstein's Autobiographical Notes, where he described physics at the point when he entered it as a graduate student, around the turn of last century, will set the stage for our inquiry. It is a daring change on the matter of principles that made modern physics possible. We'll now see how this change can percolate further.

These images are ideograms

Pictures that are worth one thousand words

Not all pictures are worth one thousand words; but these ideograms are!

Each of them will not only summarize for us the insights of a some of the last century's most original minds – but also allow us to "stand on their shoulders" and see beyond. What we'll then be able to see is a creative frontier that their combined insights reveal; and breath-taking opportunities for contribution and achievement, both fundamental and pragmatic, that this frontier offers.

By using ideograms we shall at the same time demonstrate big-picture science and its power. Recall that the philosophical systems of Hegel and Husserl took thousands of pages! Here only a handful of ideograms will prove sufficient.

Our purpose being to ignite a conversation, this concise presentation will serve us best.

Invitation to academic self-reflection

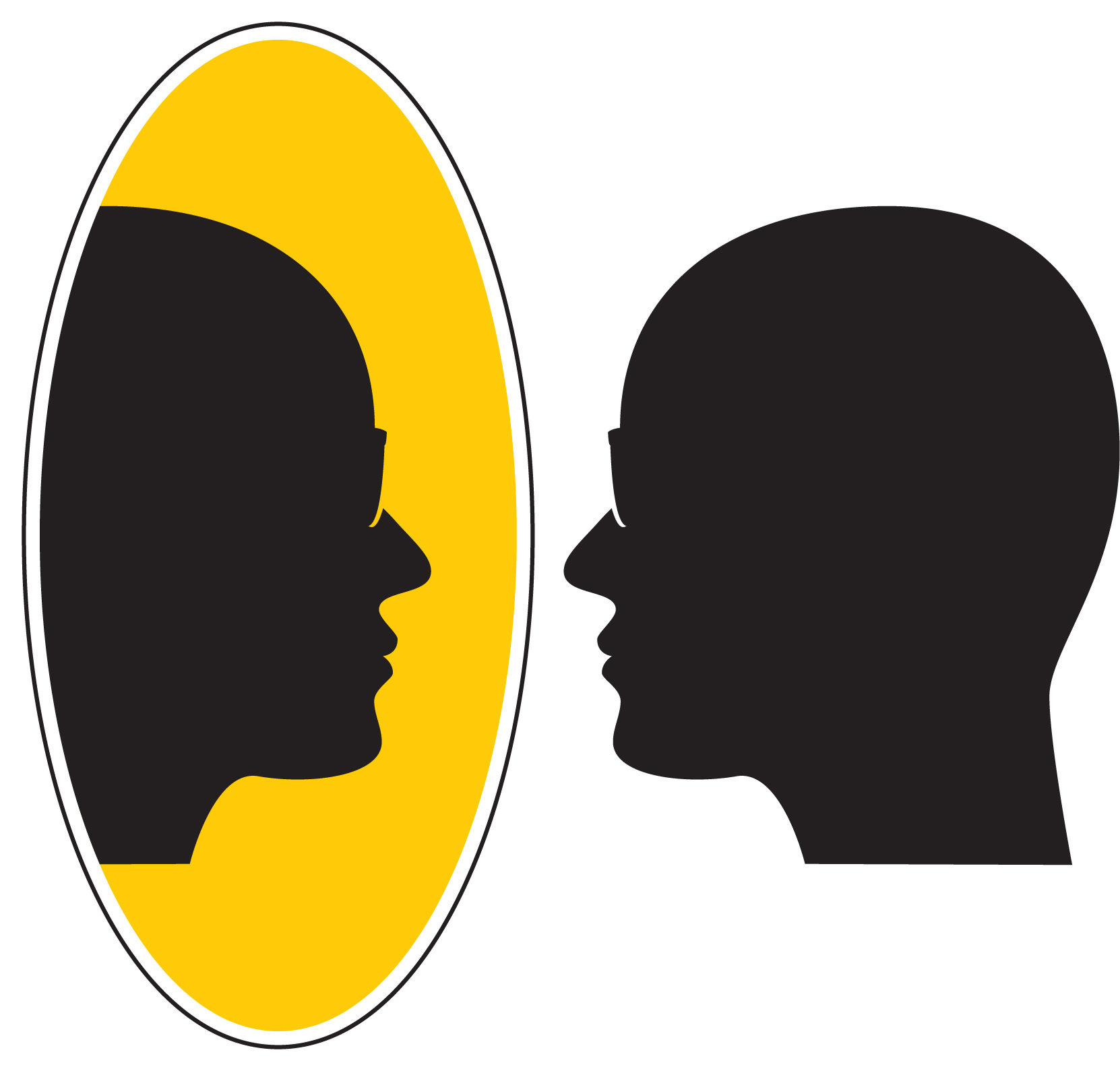

Mirror ideogram

We use this metaphorical image, of the academic mirror, to point to the nature of the academic condition to which the insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy have brought us.

Just as the case was in Lewis Carrol's story from which this metaphor has been borrowed, the academic mirror will turn out to be a trapdoor into a whole new academic reality.

You may imagine that every university campus has one – although we are normally much too busy to see it.

If we would stop and take a look, we would see in this mirror the same world that we see around us. But we would also see ourselves!

Seeing ourselves in the mirror

As a symbol, the mirror is an invitation to reconsider our conventional academic self-conception.

Seeing ourselves in the mirror symbolizes that we've understood and internalized the fact that we are not the "objective observers" we believed we were – hovering above the world, and by looking at it through the objective lense of "the scientific method", seeing it as it truly is.

In a moment we'll give you a chance to stop and reflect. How much is our academic ethos, and culture, and our general culture, marked by this self-image that we must now grow beyond?

And what is beyond?

In just a moment we'll let you pause and think about this.

But before we do that, let's hear Einstein. A couple of short excerpts, two words of wisdom, will suffice to see what needs to be seen.

The first one will explain why "the correspondence with reality" is a shaky foundation indeed.

Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world. In our endeavor to understand reality we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch. He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. If he is ingenious he may form some picture of a mechanism which could be responsible for all the things he observes, but he may never be quite sure his picture is the only one which could explain his observations. He will never be able to compare his picture with the real mechanism and he cannot even imagine the possibility or the meaning of such a comparison.

Einstein's second note will suggest that "the correspondence with reality" is a product of illusion.

During philosophy’s childhood it was rather generally believed that it is possible to find everything which can be known by means of mere reflection. (...) Someone, indeed, might even raise the question whether, without something of this illusion, anything really great can be achieved in the realm of philosophical thought – but we do not wish to ask this question. This more aristocratic illusion concerning the unlimited penetrative power of thought has as its counterpart the more plebeian illusion of naïve realism, according to which things “are” as they are perceived by us through our senses. This illusion dominates the daily life of men and animals; it is also the point of departure in all the sciences, especially of the natural sciences.

If the purpose of our pursuit of knowledge is to distinguish truth from illusion – how can we base it on a criterion that is impossible to verify? And which is itself a product of illusion?

Seeing ourselves in the world

So what is really the purpose of our (academic) pursuit of knowledge?

Or better said – what should our purpose be?

The space in front of the mirror is a space for academic self-reflection.

By seeing ourselves in the mirror, we see that the self-image of objectivity (where our task is to give to the world only that which is undeniably and unshakably solid and true; and where our inherited, disciplinary procedures give us that ability, and prerogative) can no longer be rationally maintained.

By seeing ourselves in the world, we see a world in dire need. We see ourselves as obliged to answer to our society's needs. We consider ourselves liable.

But self-reflection – however necessary it might be – is not an end in itself. It is only a beginning.

Reflection

Academia quo vadis

So here we are! This space, in front of the mirror, is exactly where we need to be.

It took us 25 centuries to come here. And so much will depend on how we'll continue!

Let's not rush ahead. Before we continue, let us make sure we understand where we are and what exactly is going on.

You may consider this whole website as an invitation to self-reflect in front of the mirror. And to develop the academic reality on the other side.

In Federation through Stories we'll share the stories of four ignored giants, who each in his own way pointed to the mirror and the reality beyond.

And in Federation through Applications you'll find a down-to-earth description of most wonderful opportunities that await in that creative realm.

In Federation through Conversations we'll see how our civilization's evolution, and our understanding of that evolution (still, of course, only in the writings of giants) brought us to this turning point.

But here, our theme is academic evolution.

This evolution has its own logic, and its own intrinsic course! The academia has its own standards of excellence. Those standards have been evolving for at least 25 centuries. We cannot just turn around, we cannot just abandon them!

Our point here is that both the intrinsic and the extrinsic or pragmatic concerns are now urging us to take the single next step in the evolution of knowledge.

What is that step?

We can go through!

The next step

This metaphorical act, of stepping through the mirror, points to a surprising, nearly magical resolution to our quest for self-identity and purpose.

What makes this apparent violation of basic laws of nature academically possible is what Villard Van Orman Quine called truth by convention.

If this is how the sciences progress – why not allow our knowledge work at large to progress similarly?The less a science has advanced, the more its terminology tends to rest on an uncritical assumption of mutual understanding. With increase of rigor this basis is replaced piecemeal by the introduction of definitions. The interrelationships recruited for these definitions gain the status of analytic principles; what was once regarded as a theory about the world becomes reconstrued as a convention of language. Thus it is that some flow from the theoretical to the conventional is an adjunct of progress in the logical foundations of any science.

Truth becomes a convention

Truth by convention is the kind of truth that is common in mathematics: "Let x be... Then..." It is meaningless to question whether x "really is" as stated.

It is the truth by convention that makes the mirror academically penetrable.

All manner of departures from the tradition – not only the departure from the scientific traditional interests and methods but also all others, including the departure from the traditional use of language (where we are obliged to inherit the meaning of words) – are made possible by truth by convention.

There is a basic convention that states this; the convention that makes all other conventions possible. We call it methodology.

Truth becomes rigorous

It stands to reason that the foundation on which we create truth and meaning must itself be as solid as possible.

The foundation we've just outlined is that for three reasons:

- It is a convention – and what's stated in that way is true by definition

- It is an expression of the epistemological state-of-the-art, as represented by the writings of giants – their insights are simply turned into conventions

- It (or more precisely the convention or methodology that defines it) is conceived as a prototype; and as all prototypes, it has provisions for updating itself when new insights are reached

Knowledge becomes useful

Just as the case is in Lewis Carrol's story, by stepping through the mirror we find ourselves in an academic reality that is in many ways a reverse image of the one we've grown accustomed to.

On the other side of the mirror we can assign a purpose to knowledge, and to our work, by stating it as a convention!

Notice that this convention is not making any claim to reality, or universality. Someone else can make another convention – and give knowledge a different purpose.

We, however, give our work the purpose we've already explained on our front page – the one pointed to by the Modernity ideogram, and the design epistemology. According to this convention, knowledge is conceived of and handled simply as a means to an end – which is a well-informed post-traditional and post-industrial society. Or to be more precise or academic – as a functional element in a larger system, which is our civilization, or society or democracy... Knowledge can then be created, evaluated and used accordingly.

By creating an epistemology by convention, we liberate knowledge and knowledge work from its age-old subservience to "reality" (and therewith also from the age-old traditional procedures and methods which presumably secured that knowledge would correspond with reality).

And by the same sleight of hand, we assign to knowledge another purpose – of helping us, contemporary people, orient ourselves in the reality we've created.

Knowledge work changes sides

By combining truth by convention with the creation of a methodology (which is an organized system of fundamental conventions), knowledge work becomes solidly established on the academic ground that Herbert Simon called "the sciences of the artificial". Those are mostly new sciences, such as computer science and economics, which do not study what objectively exists in nature but man-made things, with the goal of adapting them to their purpose.

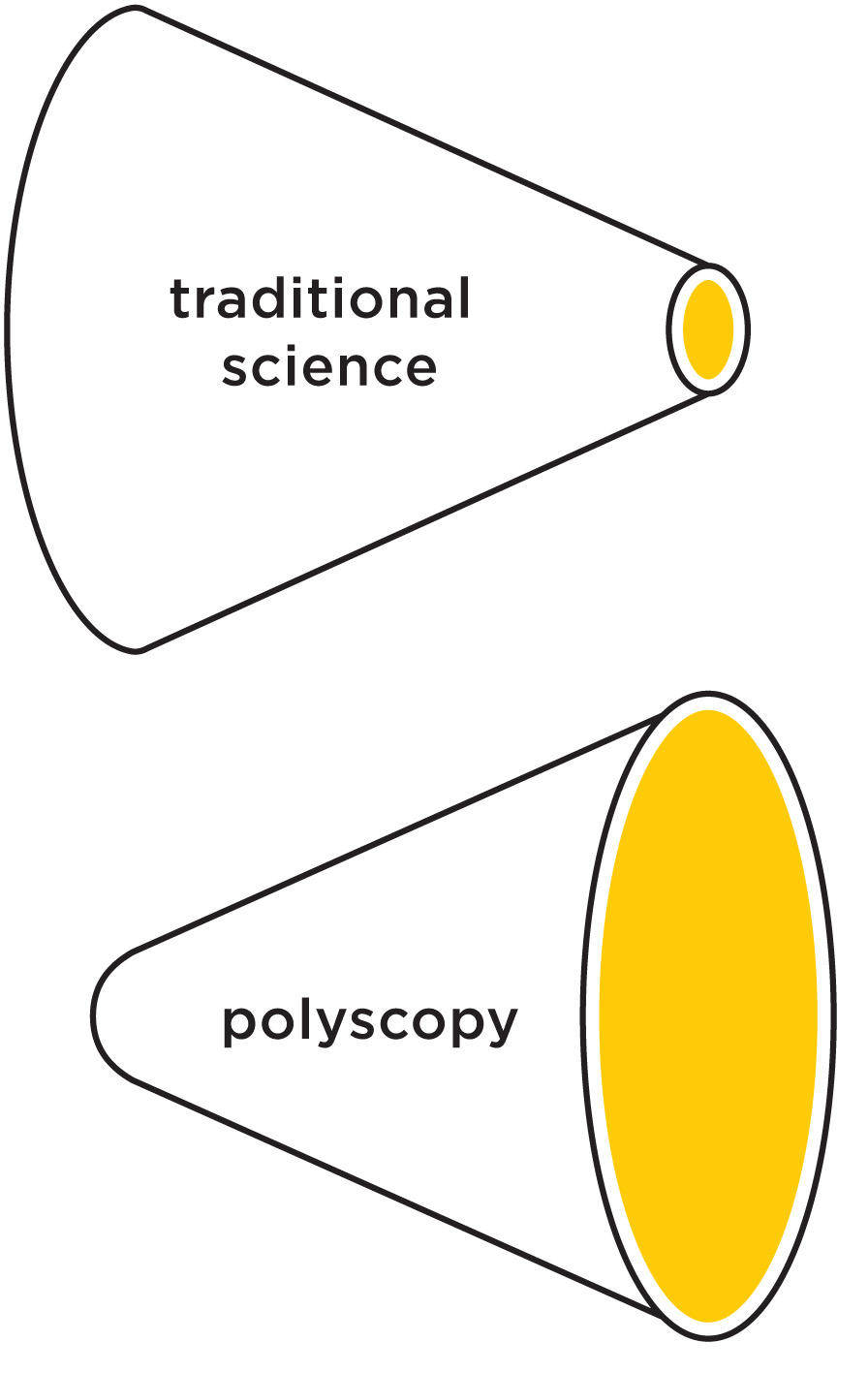

Our prototype methodology – by which all this is made concrete – is called Polyscopic Modeling. What we call polyscopy is the praxis this methodology fosters. Usually, however, we simply refer to both as polyscopy.

Knowledge federation becomes basic research

Take a moment to savor the depth and breadth of the creative frontier that is opening up. See how thoroughly our present academic order of things is allowed to change!

When our purpose is to inform the people and society, then we choose our questions according to relevance – and we answer them as well as we can, making provisions, of course, for improving those answers further.

The development of methods, technical tools and social processes that can give us the knowledge we need becomes a legitimate new notion of "basic research". So do the creative steps toward the improvement of actual knowledge-work systems.

The ignored insights and calls to action of the giants you'll meet in Federation through Stories acquire academic status, and the institutional anchoring they need and deserve.

We can liberate knowledge

Creating the way we look at the world

Our next image will point to a way to liberate academic knowledge work, or "science", from the terminology, methods and interests of traditional disciplines.

The Polyscopy ideogram stands for the fact that once we've understood that our traditional concepts and methods are human creations, which both enable us to see certain things and hinder us from seeing others – it becomes mandatory to adapt them so that we may see whatever needs to be seen.

From the pen of our giant

Science is the attempt to make the chaotic diversity of our sense-experience correspond to a logically uniform system of thought.

This, and the next quotation of our chosen giant, will give us a clue how exactly we may use the approach to knowledge we've just outlined to liberate our view of the world from disciplinary and terminological constraints.

I shall not hesitate to state here in a few sentences my epistemological credo. I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions that are laid down in books. (…) The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system. (…) All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits, just as is the concept of causality, which was the point of departure for this inquiry in the first place.

Generalizing science

Central in polyscopy is the notion of scope – which is, by definition, whatever determines what we look at and how we see it.

Building on what we've just seen, polyscopy generalizes the traditional-scientific approach to knowledge in two steps.

The first step is to allow for free definition of concepts and methods. This is, of course, made possible by defining them by convention.

As you might be guessing, that's what our keywords are – we have given them a specific meaning, by defining them in that way.

The second step is to consider also our statements or models or pieces of information as no more than – ways of looking or scopes.

Just as in Einstein's "epistemological credo", in polyscopy too there is on the one side the human experience, which is not assumed to have any a priori form. And on the other side there are our own concepts and ideas and models. Our purpose becomes to organize experience so that it sufficiently fits the scope.

We refer you to the Polyscopy prototype in Federation through Applications, and the links provided therein, to see how exactly this may work in practice.

Models are scopes

In this way polyscopy offers an answer to an interesting "philosophical" question – What do we really mean when we make a claim or state a result? (This question becomes interesting when we no longer presume that we are telling how the things "really are".)

The answer provided by polyscopy is that our statements, and models, are (by convention) just scopes, just our own created ways of looking at experience and of organizing experience. They are a way of saying "See if you can see things (also) in this way; if this may reveal to you something that you may have overlooked."

As Piaget pointed out, "Intelligence organizes the world by organizing itself"

Multiple scopes are needed

Think about inspecting a cup you are holding in your hand, to see if it's whole or cracked. You must look at it from all sides, before you can give a conclusive answer. And if any of those points of view reveals a crack – then the cup is cracked!

In polyscopy's technical language we say that to acquire a correct gestalt, all relevant aspects need to be considered.

No experiences are excluded

Another consequence of this approach to knowledge is that no experience is excluded because it fails to fit into our "reality picture".

On the contrary – since the substance of information, and of knowledge, is (by convention) human experience, then all forms of experience are considered to be potentially valuable. The method sketched here allows for combining a variety of heterogeneous insights and forms of experience to create a high-level view. Examples of this are shared below.

Simplicity and clarity are in the eyes of the beholder

Since scopes are human-made by convention, they can be as precise and rigorous as we desire – on any level of generality.

Simplicity and clarity, by convention, are "in the eyes of the beholder"; they are a consequence of our scope! It is legitimate to make them clear and simple – even in a complex world.

This is legitimate because our models are never complete; they are never the reality. Anything we say is (by convention) a simplification, an angle of looking, and what that angle of looking reveals.

Descartes would agree

The overall result is a general-purpose method which – like a portable flashlight – can be pointed at any phenomenon or issue.

The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it brings solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.

René Descartes is often "credited" as the philosophical father of the limiting (reductionistic) aspects of science. This Rule 1 from his manuscript "Rules for the Direction of the Mind" (unfinished during his lifetime and published posthumously) shows that also Descartes might have preferred to be remembered as a supporter of polyscopy.

Growing knowledge upward

Science on a crossroads

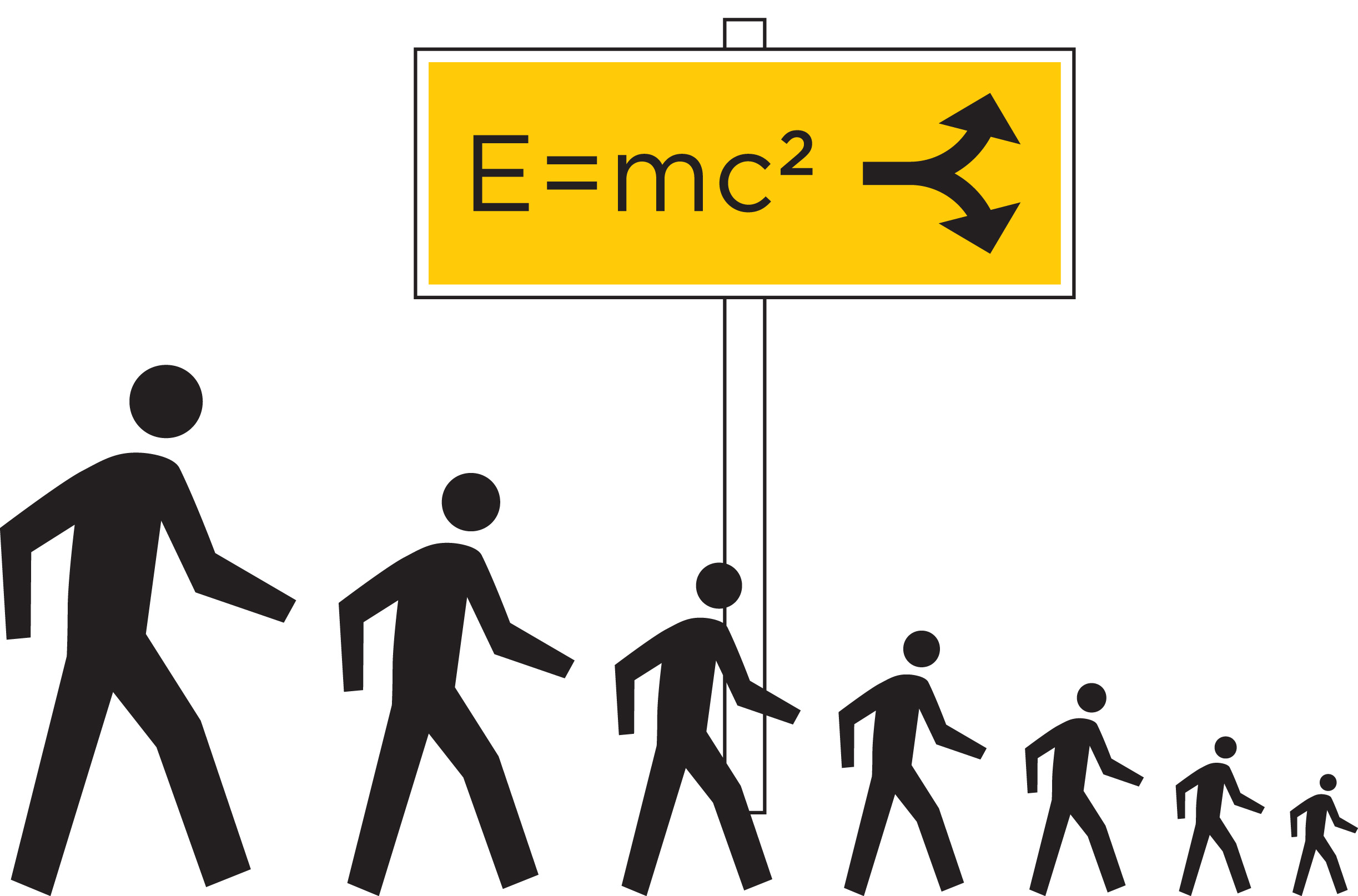

The Science on a Crossroads ideogram points to the possibility to reverse the narrow and technical focus in the sciences – and create general insights and principles about any theme that matters.

The Science on a Crossroads ideogram depicts the point in the evolution of science when it was understood that the Newton's concepts and "laws" were not parts of the nature's inner machinery, which Newton discovered – but his own creation, and an approximation. Two directions of growth opened up to science – downward, and upward. The sequence of scientists "converging to zero" in the ideogram suggests that only the "downward" option was followed.

The moment when this happened

It has turned out that the very moment when science reached those crossroads has been recorded!

In his "Autobiographical Notes", after describing how the successes of science that resulted from Newton's classical results led to a wide-spread belief that there wasn't really much more than that, as we saw above, Einstein discusses on a couple of pages the anomalies, results of experiments and observed phenomena that were not amenable to such explanation. He then concludes:

Enough of this. Newton, forgive me; you found just about the only way possible in your age for a man of highest reasoning and creative power. The concepts that you created are even today still guiding our thinking in physics, although we now know that they will have to be replaced by others further removed from the sphere of immediate experience, if we aim at a profounder understanding of relationships.

Why the direction "up" was ignored

The direction "up" is a natural direction for the growth of anything – and of knowledge in particular. Hasn't the insight, the wisdom, the general principle, always been the very hallmark of knowledge? So why did science continue its growth only downward – toward more technical, more precise – and more obscure results?

The reason is obvious, and it is also suggested by Einstein: It had to be done, "if we aim at a profounder understanding of relationships" – that is, of natural phenomena. They turned out to be far more complex than it was originally believed.

The bottom-level reality picture turned out to be retreating ever deeper – as the scientists aimed "at a profounder understanding of relationships".

So why not do as Newton did in all walks of life i.e. wherever solid knowledge is needed – create approximate models that serve us well enough?

The answer is obvious. The disciplinary organization of knowledge had already taken shape. Einstein being "a physicist", his job was to study the physical phenomena, in terms of the masses and velocities and mathematical formulas.

The job of updating the whole production of knowledge – and the job of creating high-level insights – happened to be in nobody's job description. And hence they remained undone.

Think of Knowledge federation as a road sign or banner, demarcating the creative frontier on which this oversight can be corrected.

Redirecting knowledge work

Illuminating what's hidden

Polyscopy, as we've just outlined it, is like a flexible searchlight, which can be pointed in whatever direction we choose.

The methodology provides specific criteria (in place of the traditional "correspondence with reality") to orient the all-important choice of scope (what we'll be looking at, and in what way). One of them is the perspective.

The perspective criterion postulates that every thing or issue has a visible and a hidden side. And that the purpose of knowledge work is to illuminate what is hidden, and make the whole visible in correct shape and proportions.

Gestalt criterion

The criterion by which polyscopy reorients knowledge to grow upward is gestalt, as we have seen on the front page.

By convention, having a correct gestalt is what "being informed" is all about. You may know the exact temperature i every room, and even the CO2 percentages in the air. But it is only when you know that your house is on fire that you know that you need to evacuate the house and call the fire brigade.

Knowledge federation in two pictures

Information

At the risk of oversimplifying, we may now re-introduce to you the work of knowledge federation as correcting the perspective to acquire a correct gestalt.

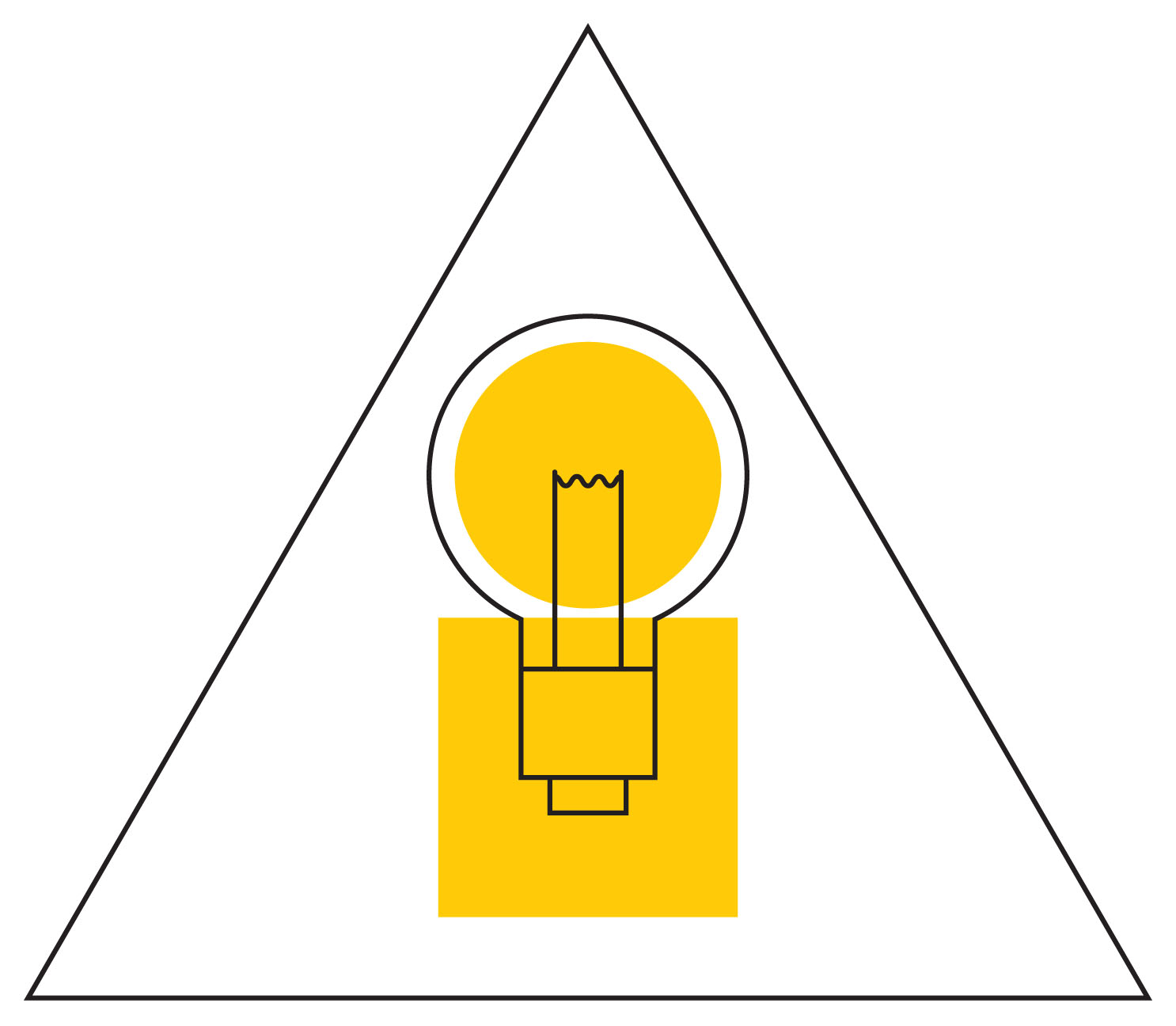

The Information ideogram points to the structure of the information that knowledge federation aims to produce. Or metaphorically, to the principle of operation of the 'light bulb'.

The “i” in this image (which stands for "information") is composed of a circle on top of a square. Think of the square as providing the perspective; and of the circle as depicting the gestalt.

The square stands for the technical and detailed low-level information. The square also stands for examining a theme or an issue from all sides. The circle stands for the general and immediately accessible high-level information. This ideogram posits that information must have both.

And that without the former, without the 'dot on the i', the information is incomplete and ultimately pointless.

This ideogram also suggests how to establish or justify the high-level views – by founding them on low-level ones. And by 'rounding off', by 'cutting corners'.

Knowledge

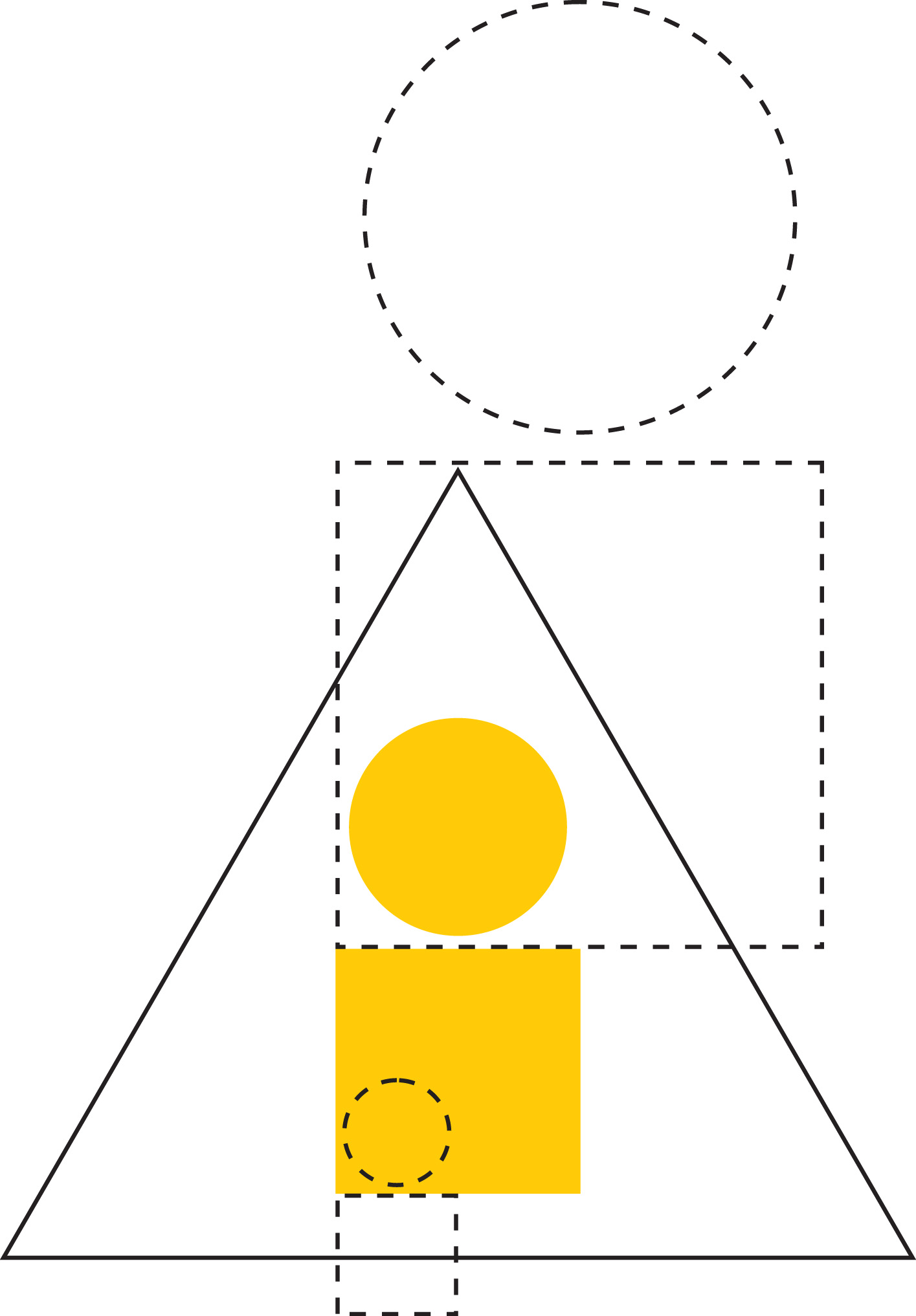

The Knowledge ideogram depicts knowledge federation as a process – and also the kind of knowledge that this process aims to produce.

It follows from the fundamentals we've just outlined that (when our goal is to inform the people) knowledge federation will do its best to federate knowledge according to relevance – and adapt its choice of scope to that task. The rationale is that "the best available" knowledge will generally be better than no knowledge at all.

Knowledge, and information, are envisioned to exist within a holarchy – where the low-level "pieces of information" or holons serve as side views for creating high-level insights. Multiple and even contradictory views on any theme are allowed to co-exist. A core function of federation as a process is to continuously negotiate and re-evaluate the relevance and the credibility of those views.

Two examples

Convenience paradox

Redirecting our "pursuit of happiness" is of course a natural way to give a new direction to our 'bus'. Informing our "pursuit of happiness" is also a natural application where the ideas presented above can be put to test.

The Convenience Paradox ideogram depicts a situation where the pursuit of a more convenient direction (down) leads to an increasingly less convenient condition. The human figure in the ideogram is deciding which way to go. He wants his way (of life) to be more easy and pleasant, or more convenient. If he follows the direction that seems more convenient, he will end up in a less convenient condition – and vice versa.

By representing the way to happiness as yin (which stands for dark, or obscure) in the traditional yin-yang ideogram, it is suggested that the way to convenience or happiness must be illuminated by suitable information.

This ideogram is of course only the high-level part, the circle or the 'dot on the i'. Its low-level part or justification consists of a variety of insights emanating from a broad variety of giants and traditions. The rationale is to select the ones that resulted from the experience of working with large numbers of people – and which have something important to tell us about our civilized condition; and about ways in which this condition could be radically improved.

An example is the above core insight of F. M. Alexander, the founder of a therapy school called "Alexander Technique", which is now being taught worldwide.The process of civilization, according to Alexander, has contaminated man’s biological and sensory equipment, with a resultant crippling in the responses of the whole organism. Tension and conflict are more and more substituted for coordination.

The world traditions pointed to the nature of "the way" (to happiness or fulfillment, represented by the dark Yin part of the ideogram) by giving it different names such as "Tao", "Do", "Yoga", "Dharma" and "Tariqat". Considered together, they enable us to model the most interesting range of possibilities we are calling "happiness between one and plus infinity" – which is a direction in which our civilization's "progress" may most naturally continue.

We'll say more about this theme in Federation through Conversations – where we'll also initiate a conversation to collectively refine it and develop it further.

Power structure

As a way of looking at the world or scope, the power structure empowers us to conceive of the traditional notions of "power holder" and "political enemy" in an entirely new way – and to reorient our ethical sensibilities and our political action accordingly.

The Power Structure ideogram depicts the power structure as a structure, where seemingly distinct and independent entities such as monetary or power interests, the ideas we have about the world, and our own condition or health are tied together with subtle links, so that they evolve and function in co-dependence and synchrony.

In "A Century of Camps" Zygmunt Bauman explained how even massive and unthinkable cruelty (of which the Holocaust is an example) can happen as a result of no more than (what we are calling) the structure of the system – and people just "doing their jobs".

The power structure model explains in what way exactly malignant societal structures can evolve by the conventional "survival of the fittest".

To legitimize the view in which a complex structure (and not a person or group endowed with intelligence and identifiable interests) is considered "the enemy", insights from a range of technical fields including combinatorial optimization, artificial intelligence and artificial life are combined with insights from the humanities – including Bauman's just mentioned one.

An effect of this model (central to the paradigm strategy we are presenting as our larger motivating vision) is that it entirely changes the nature of the political game, from "us against them" to "all of us against the power structure".

By revealing the subtle links between our ideas about the world and power interests, the power structure helps us understand further why a new phase of evolution of democracy, marked by liberation and conscious creation of the ways in which we look at the world, is a necessary part of our liberation from renegade and misdirected power.

Reflection

How to begin the next Renaissance

What new insights may relish the next Renaissance-like change? What might be its battle cries?

In what way may the approach to knowledge we've just described help foster such insights?

The two examples we have just seen, described thus far rather dryly, betray exemplary answers to such questions.

Happiness and culture

Our theme is what Peccei called "a great cultural revival" – a radical improvement of "human quality" across the board.

Presently, our "pursuit of happiness" is conspicuously steered by what Einstein branded "plebeian illusion of naïve realism" – we experience something as attractive, and continue to consider it as such. Not only is the power of our technology directed toward amassing such "pleasurable" things – also is the power of our information directed toward reinforcing this error of perception!

The Convenience Paradox ideogram points to a way to correct that. The gestalt it fosters is that this naïve "pursuit of happiness" is as little sensible as always going downward, because that feels easier.

What needs to be illuminated to correct the perspective and reach this gestalt is the long-term consequences of what we do. The way to happiness – and the nature of the condition to which the way we are following is leading us.

It might be useful at this point (where we are connecting the dots) to look at the definition of culture we presented in Federation through Application, which emphasizes cultivation. This definition is built on the metaphor of planting and watering a seed. Notice what this metaphor is saying between the lines: To have a culture, we cannot rely on mechanistic "scientific" explanations and reasoning (a dissection and analysis of a seed will not reveal that the seed should be planted and watered). To have a culture, we must rely on direct human experience (that certain kinds of cultivation lead to a certain effect).

In the justification of the Convenience Paradox result a variety of insights are woven together, to show that spectacularly higher levels of wellbeing or "happiness" are reachable through certain kinds of cultivation.

We already own more than enough of such specific insights to reach this larger one.

Not being amenable to "scientific" explanation and interests, those insights have remained on a cultural margin called "alternative culture" – and with only a marginal effect on everyday reality.

Social justice and democracy

The second example points to a way to redirect another powerful drive – for power. And for justice. Can the zoon politikon perceive his interest in a new way – and change course?

The question here is (to go straight to the point) – If all the world's power is in the hands of the powerful, in what way can the balance of power change enough for structural change to become possible?

The key insight here is that the "the game" (or the power structure or system) determines not only who will be the winners and the losers, but also our very idea of what winning and losing is about! The power structure as a way to looking at this issue reveals that when subtle relationships between our ideas, our wellbeing and the interests of the power structure we have internalized as our own – then we can in a real sense choose "what our purposes are to be"!

The power structure gestalt points to pathological (cancer-like) growth of our systems. Our choice then becomes whether to be part of the disease – or the remedy.

A likely effect on our socialized notion of "success" is what the Adbusters called "decooling". Not long ago it was "cool" to smoke a big cigar in an airplane; it's not any more.

Putting the two together

An especially enlightening effect is reached by combining the above two insights.

Their combination is found in a vivid form in the history of the world religions – where a re-discovery of the way to liberation invariably led to a new institution – and a new power structure! This is what the Liberation book (the first in Knowledge Federation trilogy) is about. While this book is being written, the Garden of Liberation prototype (in Federation through Applications) will provide the details.

Discovery of ourselves

We are now standing in front of another mirror, larger than the previous one.

How do we feel? Can we feel deep love, or charity or awe? We are the instruments on which the melody of emotion is played.

The power structure brings a similarly shocking realization to our quest for justice – that "the enemy is us". And that our own behavior, and the values from which it stems, is the "enemy" we need to face.

All these are of course only hints. The details must be seen and digested before the hints can become guiding insights.

And yet you may already anticipate why also our societal anomalies may be resolved – unexpectedly, almost magically – by stepping through the mirror!