Difference between revisions of "Holotopia: Five insights"

m |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

<p>We <em>federate</em> information from a broad variety of cultures, historical eras and sources, to illuminate the <em>way</em> to human fulfillment.</p> | <p>We <em>federate</em> information from a broad variety of cultures, historical eras and sources, to illuminate the <em>way</em> to human fulfillment.</p> | ||

<p>Lacking such information, and following our general cultural bias, we've confused happiness with <em>convenience</em>—i.e. with what <em>appears</em> as attractive at the moment. Needless to say, this error of perception has been endlessly amplified by advertising.</p> | <p>Lacking such information, and following our general cultural bias, we've confused happiness with <em>convenience</em>—i.e. with what <em>appears</em> as attractive at the moment. Needless to say, this error of perception has been endlessly amplified by advertising.</p> | ||

| − | <p>We use the <em>holoscope</em> to show that <em>convenience</em> is a deceptive, illusory value. And that in the shadow of this delusion, an endless possibilities for improving our lives—through <em>human development</em>—are waiting to be uncovered.</p> | + | <p>We use the <em>holoscope</em> to show that <em>convenience</em> is a deceptive, illusory value. And that in the shadow of this delusion, an endless possibilities for improving our lives—through <em>human development</em>—are waiting to be uncovered.</p> |

| + | <p>We show that this turn of our fortunes can be made by pursuing <em>wholeness</em>, not <em>convenience</em>.</p> | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

<div class="col-md-7"> | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | At the turn of the 20th century it appeared that the technology would liberate us | + | At the turn of the 20th century, it appeared that the technology would liberate us from drudgery and toil, and empower us to engage in finer human pursuits. But we seem to be more busy and stressed than ever! What happened with all the time we've saved? |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | <p>We look at <em>the systems in which we live and work</em>. Imagine them as gigantic machines, comprising people and technology, whose function is to take our daily work as input, and turn it into socially useful effects. If we are stressed and busy—should we not see if <em>they</em> might be wasting our time? And if the result of our best efforts are problems rather than solutions—should we not see whether <em>they</em> might be causing those problems?</p> | |

| − | <p>We look at <em>the systems in which we live and work</em>. Imagine them as gigantic machines, comprising people and technology, whose function is to take our daily work as input, and turn it into socially useful effects. If | + | <p>We <em>federate</em> insights from a variety of sources, including both technical sciences and the humanities, to develop a <em>view</em> where <em>the systems in which we live and work</em> are seen as <em>power structures</em>—which are both <em>results</em> of power struggle, and <em>implements</em> of disempowerment.</p> |

| − | + | <p>Those insights show that there <em>is no</em> "invisible hand", which we can rely on to turn our self-serving acts into the greatest common good. As the Modernity <em>ideogram</em> might suggest, <em>enormous</em> improvements of our condition can be reached by deliberately making our <em>socio</em>–technical systems more <em>whole</em>. | |

| − | |||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Collective mind</h2></div> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>[[Holotopia:Collective mind|Collective mind]]</h2></div> |

<div class="col-md-7"> | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 09:16, 6 May 2020

Contents

- 1 H O L O T O P I A P R O T O T Y P E

- 2 Five Insights

- 2.1 Convenience paradox

- 2.2 Power structure

- 2.3 Collective mind

- 2.4 Socialized reality

- 2.5 Narrow frame

- 2.6 Sixth insight

- 2.7 The five insights are inextricably related

- 2.8 Large change can be easy

- 2.9 What is really going on

- 2.10 Ten dialogs

- 2.11 Co-opt Wall Street—the Future of Business

- 2.12 Cybernetics and the Future of Democracy

- 2.13 Ludens—A Recent History of Humankind

- 2.14 Future Science

- 2.15 Liberation—The Future of Religion

- 2.16 From One to Infinity—The Future of Happiness

- 2.17 How to Put an End to War

- 2.18 Largest Contribution to Knowledge

- 2.19 From Zero to One—The Future of Education

- 2.20 Future Art

H O L O T O P I A P R O T O T Y P E

Five Insights

The Renaissance liberated our ancestors from preoccupation with the afterlife, and empowered them to seek happiness here and now. Their lifestyle changed, and culture blossomed. Have we followed the pursuit of happiness to its end? Or could a surprising new turn, a "change of course", still be possible?

We federate information from a broad variety of cultures, historical eras and sources, to illuminate the way to human fulfillment.

Lacking such information, and following our general cultural bias, we've confused happiness with convenience—i.e. with what appears as attractive at the moment. Needless to say, this error of perception has been endlessly amplified by advertising.

We use the holoscope to show that convenience is a deceptive, illusory value. And that in the shadow of this delusion, an endless possibilities for improving our lives—through human development—are waiting to be uncovered.

We show that this turn of our fortunes can be made by pursuing wholeness, not convenience.

At the turn of the 20th century, it appeared that the technology would liberate us from drudgery and toil, and empower us to engage in finer human pursuits. But we seem to be more busy and stressed than ever! What happened with all the time we've saved?

We look at the systems in which we live and work. Imagine them as gigantic machines, comprising people and technology, whose function is to take our daily work as input, and turn it into socially useful effects. If we are stressed and busy—should we not see if they might be wasting our time? And if the result of our best efforts are problems rather than solutions—should we not see whether they might be causing those problems?

We federate insights from a variety of sources, including both technical sciences and the humanities, to develop a view where the systems in which we live and work are seen as power structures—which are both results of power struggle, and implements of disempowerment.

Those insights show that there is no "invisible hand", which we can rely on to turn our self-serving acts into the greatest common good. As the Modernity ideogram might suggest, enormous improvements of our condition can be reached by deliberately making our socio–technical systems more whole. </div> </div>

The printing press revolutionized communication, and enabled the Enlightenment. Without doubt, the Internet and the interactive digital media constitute a similar revolution, which is well under way. Are we really calling that a 'candle'?

Scope

<p>In the manner that we just outlined, we consider the people connected by technology as a gigantic system, a collective mind. And we look at the 'program' or process, which constitutes our collective mind's very principle of operation. </p>

View

<p>Once again we've adopted something from the past, without considering the options. By using the principle that the printing press made possible—broadcasting—we've failed to take advantage of their main distinguishing trait.</p> <p>Far from giving us the awareness we need, the new technology is keeping us dazzled. Instead of empowering us to see and change our world, it keeps us overwhelmed, and passive.</p> <p>A radically better way to use the information technology is now possible, and also necessary. To make it a reality, our relationship with information, and with technology, need an update.</p>

Action

<p>Just as the human mind does, our collective mind must federate knowledge; not merely broadcast information.</p>

Federation

<p>The new media were created to enable the change we are proposing—a half-century ago, by Douglas Engelbart and his SRI-based team. And Engelbart too was following the lead suggested by Vannevar Bush, already in 1945. </p> <p>The non-technical, humanities side of this coin is no less interesting. Already Friedrich Nietzsche warned us that the overabundance of impressions is leaving us dumbfounded, unable to "digest" the overload of impressions and to act. Guy Debord, more recently, contributed far-reaching insights, which now need to be carefully digested. </p> <p>The prototypes here include the knowledge federation as a transdiscipline—which is offered to serve as an evolutionary organ, and supplement the function our society, and academia are lacking.</p>

Socialized reality

At the core of the Enlightenment was a profound change of our way to truth and meaning—from seeking them in the Bible, to empowering the reason to find new ways. Galilei in house arrest was our reason that was kept in check, and barred from taking its place in the evolution of ideas. Have we reached the end of this all-important evolutionary process, which Socrates and Plato initiated twenty-five centuries ago? Can the academia still make a radical turn, and guide our society to make an even larger one?

Scope

<p> The Socialized Reality insight is about the fundamental assumptions that serve as the foundation on which truth and meaning are created. It is also about a possibility that a deep change, of the foundation, may naturally lead to a sweeping change, "a great cultural revival"—as the case was during the Enlightenment.</p> <p> We look at the very foundations, that is—the fundamental assumptions, based on which truth and meaning are constructed. Being the foundations that underlie our thinking, they are not something we normally look at and think about. It is, indeed, as if those foundations were hidden under the ground, and now need to be escavated.</p>

View

<p>Without even noticing that, from the traditional culture we've adopted a myth incomparably more subversive than the myth of creation. This myth now serves as the main foundation stone, on which the edifice of our culture has been built.</p> <p>By conceiving our pursuit of truth and meaning as a "discovery" of bits and pieces of an "objective reality" (and thus failing to perceive truth and meaning, and information that conveys them, as an essential part of the 'machinery' of culture), we've at once damaged our cultural heritage—and given the instruments of cultural creation away, to the forces of counterculture. In our present order of things anything goes—as long as it does not explicitly contradict "the scientific worldview".</p> <p>While the counterculture is creating our world, the scientists are caught up in their traditional "objective observer" role...</p>

Action

<p>We show how a completely new foundation for truth and meaning can be constructed—which is independent of any myths and unverifiable assumptions. On this new foundation, a completely new academic and societal reality can be developed.</p> <p>This new foundation can be developed by doing no more than federating the information we already own.</p> <p>Federating knowledge means not just "connecting the dots", but also making a difference.</p>

Federation

<p>To show that the correspondence of our models with reality is a myth (widely held belief that cannot be rationally verified), it is sufficient to quote Einstein (as a popular icon of modern science). But since we are here talking about the very foundation stone on which our proposal has been developed, we take this federation quite a bit further.</p> <p>An essential point here is to understand "reality" as an instrument that the traditional culture developed to socialize us into a worldview, and its specific order of things or paradigm. By understanding socialization as a form of power play and disempowerment, we provide in effect a mirror which we may use to self-reflect, and see our world and our condition in a new way. The insights of Pierre Bourdieu and Antonio Damasio are here central. A variety of others are also provided.</p>

Narrow frame

Science replaced the faith in the bible and the tradition. The revolutionary changes that resulted gave us powers that people a few generations ago couldn't even dream of. We can not be calling that a 'candle'?

Scope

<p>We look at science as an instrument that expands, but also determines and confines our vision. We take off our 'eyeglasses', and we take a closer look.</p>

View

<p>Science was never created for the role in which it now finds itself—the role which Benjamin Lee Whorf branded "the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture". Science found itself in that role by proving its superiority on a much narrower terrain—where causal explanations of natural phenomena are found. </p> <p>Consequently science constitutes—as Werner Heisenberg pointed out—a narrow frame, a way of looking at the world that for some purposes served some purposes well (notably developing science and technology), and other purposes quite poorly (notably the development of culture, which would enable us to use the power of technology meaningfully and safely). </p> <p>An even more basic problem is that science constitutes a fixed and narrowly focused way of looking at the world. It has been said that to a person with a hammer in his hand everything looks like a nail. Are even the best among us doomed to explore the world by just endlessly looking for the next 'nail'?</p>

Action

<p>By federating knowledge, a general-purpose methodology can be developed, which preserves the prerogatives of science, and avoids its disadvantages. This way to knowledge enables us to choose our themes according to relevance; and to create guiding insights in all walks of life—and on any desired level of generality or detail.</p>

Federation

<p>Again quoting Einstein is sufficient. Werner Heisenberg, however, provided us a direct formulation of the narrow frame insight; and also an explanation why the modern physics constitutes a rigorous disproof of the fundamental premises on which the narrow frame has been adopted as the method by which we pursue truth and meaning.</p> <p>Our prototypes show how the narrow frame evolution can be reversed.</p>

Sixth insight

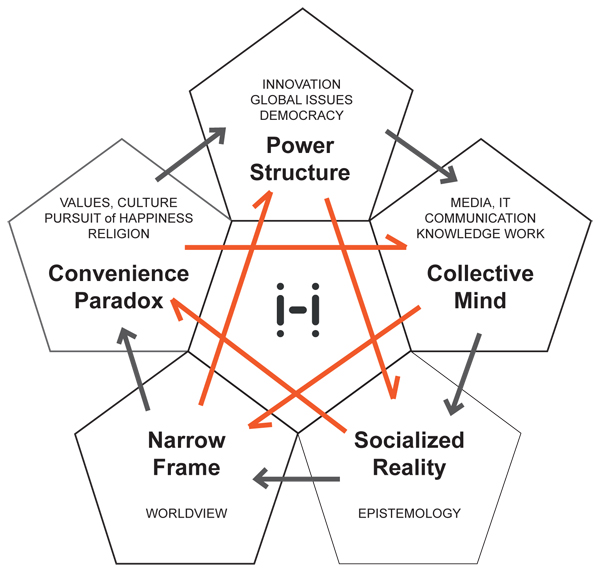

The five insights are inextricably related

By putting the five insights together, a larger, new, overarching insight results.

The black arrows form a vicious cycle

<p>We may now follow the black arrows in the Five Insights ideogram, and see that the anomalies that are linked by those arrows cause or create one another:

- By using narrowly conceived self-interest as guiding light (which we here called convenience), we co-create, without seeing that, destructive power structures

- Our inability to see and reconfigure our collective mind is just a special case of the anomaly we called power structure

- Lacking information that can 'show us the way', we have no other recourse but to be socialized to accept the present paradigm as "the reality"

- Once we've adopted "mirroring reality" to be what truth and information are about—then it follows as a natural consequence to adopt the traditional science as the method by which truth and meaning are created

- Since the narrow frame tells us next to nothing about the possibilities of "human development", we had no other resort but to "pursue happiness" by pursuing convenience

</p>

The red arrows form a benign cycle

<p>The red arrows show that we cannot really change one of the insights they connect together, without also changing the other.</p>

- To step beyond the convenience paradox and develop the "human quality" (as Aurelio Peccei claimed we must), our collective mind must be able to federate the insights that illuminate the way; to begin to transform our collective mind (which we offered as the natural place to begin or the leverage point for transforming our situation), our values must enable us to forego turf strife, and begin to self-organize

- The power structure and the socialized reality are really just two sides of a single coin—which are the 'hardware' and the 'software' side of our societal order of things: The power holder (power structure) has once again acquired the prerogative to legitimize itself and make itself virtually invisible—by socializing us to accept it as "reality"

- Similarly, the collective mind and the narrow frame are the 'hardware' and the 'software' aspects of our knowledge work

- We cannot see through the convenience paradox, by including ourselves in the equation—unless our culture gives us the capability to 'see ourselves in the mirror'

Large change can be easy

<p>We can now see why a comprehensive change can be easy, even when smaller and obviously necessary changes may have proven impossible. The strategy that defines the holotopia naturally follows: Instead of struggling with any of the details, we focus on changing the order of things as a whole.</p> <p>And here, changing the way in which we look at the world and see the world is of course the key.</p> <p>So we may not need to occupy Wall Street. But we may need to occupy the university! It is immensely good news that our future is not in the hands of the professionals whose social function is to turn money into more money—but in the hands of publicly sponsored intellectuals! </p> <p>The changes we want to see in the world, including all those holotopian ones that vastly surpass our highest hopes—can be triggered in the most natural way by carrying the evolution of knowledge a step further.</p>

What is really going on

<p> One of our prototypes is a book manuscript titled "What's Going On?", and subtitle "A Cultural Revival". The point was to re-define what constitutes the news; and the spectacle. What's presented in the book is a most spectacular moment in human history, which we are living through right now.</p> <p>The "problems" we are experiencing are like cracks in the walls of a house whose foundations are failing. Indeed (when we dig a bit under the surface of things and take a look)—there aren't any foundations, really, to speak about. What's there has never been constructed. We are just building on whatever terrain things happened to be placed. Just building further. And higher. </p>

Ten dialogs

The five insights here present us with a context within which age-old themes and challenges can be explored and understood in a completely new way—in the context of the emerging paradigm, the holotopia.

<p>Hence we here, in this context, open the dialogs on fifteen most timely themes—which we label by the five insights, and their ten direct relationships. Since we've already seen the insights, only ten conversations remain to be described.</p> <p>We provide here only the titles and some hints—and leave it to the dialogs to unpack their meaning, and develop it further.</p>

Co-opt Wall Street—the Future of Business

<p>The Co-opt Wall Street—the Future of Business conversation takes place in the context provided by the Convenience Paradox insight and the Power Structure insight.</p>

<p>How can the emerging re-evolution have enough power to overthrow the powerful? No conflict of power is needed; we can just simply co-opt them!</p> <p>The power and the powerful, as we've come to perceive them, are both part and parcel of the power structure. The key is to see that our real interests, both personal and global, run counter to the interests of the power structure. </p> <p>The Adbusters left us a useful concept, "decooling"; a decooling of the popular notions of success and power is ready to take place.</p>

Cybernetics and the Future of Democracy

<p>Cybernetics has taught us that to be governable, a system must have a certain minimal structure—which our systems, and notably our democracies, do not have. Can anyone be in control—in a bus with candle headlights?</p> <p>Here belongs also the Wiener's paradox—the easily demonstrable fact that the information, as produced in academia has lost its agency (capability to be turned into knowledge, and action). The Wiener–Jantsch–Reagan thread, detailed in Federation through Conversations, provides a suitable springboard story (and we may make this conversation a jour by adding also Donald Trump). </p>

Ludens—A Recent History of Humankind

<p>The Ludens—A Recent History of Humankind conversation combines the Collective Mind insight and the Socialized Reality insight.</p>

<p>While we may be biologically equipped to evolve as the homo sapiens, we have in recent decades devolved culturally as the homo ludens, man the (game) player—who shuns knowledge and merely learns his various roles, and plays them out competitively. </p> <p>The point here is to see that our collective mind being as it is (mostly only broadcasting knowledge), we have no other recourse but to deal with the complex reality in the homo ludens way—i.e. by being socialized into our roles.</p> <p> The Nietzsche–Ehrlich–Giddens thread, detailed in Federation through Conversations, may provide a suitable start.</p>

Future Science

<p>Here we take up the academic dialog in front of the mirror: Has science become a "plagiarist of its own past", as Benjamin Lee Whorf warned us?</p> <p>Can the academia now make a decisive step 'through the mirror' (by redefining the relationship we as culture have with information)—and lead our society to the other side?</p>

Liberation—The Future of Religion

<p>In the traditional societies, religion has played the all-important role of connecting the people to an ethical purpose, and to each other. Heisenberg made a case for the narrow frame insight by pointing the demolition of religion it caused, and the erosion of values that resulted. Can this trend be reversed?</p> <p>Can we put an end to religion-inspired hatred, terrorism and conflict—by evolving religion further?</p> <p>The story of Buddhadasa's rediscovery of the Buddha's original insight—in which he recognized the essence of all religion—might be a natural way to begin. The point here is to (create a way to knowledge that enables us to) perceive the liberation from any narrow frame—religions or scientific—and indeed from all forms of egoism and hence of power structure and power-based identity, as the very core of the Buddha's teaching, and as an enlightened way to happiness. </p>

From One to Infinity—The Future of Happiness

<p>All we know about happiness is in the interval between zero (complete misery) and one ("normal" happiness); but what about the rest? What about the happiness between one and plus infinity?</p> <p>This conversation is about the humanity's best kept secret—that there are realms of thriving and fulfillment, beyond what we've experienced and know it exists. </p> <p>While (related to convenience paradox) we defined culture and cultivation by analogy with cultivation of plants, there is a core difference here that needs to be overcome through concerted action: The results of inner cultivation cannot be seen!</p> <p>Could this insight constitute the very 'carrot' that Peccei might have been looking for?</p>

How to Put an End to War

<p>Alfred Nobel had the right idea: Empower the creative people and their ideas, and the humanity's all-sided progress will naturally be secured. But our creativity, when applied to the cause of peace, has largely favored the palliative approaches (resolving specific conflicts and improving specific situations), and ignoring those more interesting curative ones. What would it take to really put an end to war—once and for all? </p> <p>A combination of the power structure insight and the socialized reality insight will help us see why putting an end to is realistically possible: The war is only possible when we live in a worldview which we've been socialized to accept as "reality" by the power structure! </p> <p>The Chomsky–Harari–Graeber thread, discussed in Federation through Conversations, will provide us a suitable start.</p>

Largest Contribution to Knowledge

<p>It is easy to see (and we've shown that already) why the systemic contributions to human knowledge (improvements of the 'algorithm' by which knowledge is handled in our society) are incomparably larger than specific contributions of knowledge. But there is a contribution to human knowledge that is still larger—the contribution of a way in which the systemic solutions for knowledge work can continuously evolve!</p> <p>This conversation is, in other words, about our proposal to add knowledge federation to the academic repertoire of fields—and thereby the capability to evolve knowledge and knowledge-work systems by federating knowledge.</p> <p>Such federation, of course, involves working with the collective mind as systems or 'hardware', and with the narrow frame as methods or 'software'</p>

From Zero to One—The Future of Education

<p>In the context of those two insights, it is easy to see why, as Ken Robinson pointed out, "education kills creativity": Education has largely evolved as a way to socialize people into a "reality picture", and hence as an instrument of power structure. What sort of people does the power structure need? The MIddle Ages needed to socialize people to give their bodies to the king, and their minds to the Church. What do the contemporary power structures need?</p> <p>The title of this conversation is adapted from Peter Thiel's book, where it's intended to point to a certain kind of creativity. We know all about taking things that already exist from one to two, and to three and up to one hundred and beyond. What we need is the capability to conceive of and create things that do not yet exist.</p> <p>Can we conceive an education that has no longer socialization, but "human development" as goal? </p>

Future Art

<p>The Future Art conversation takes place in the context of the Narrow Frame insight and the Power Structure insight. </p> <p>Art has always been an instrument of cultural reproduction; and on the forefront of social change. When Duchamp exhibited the urinal, he challenged the traditional conception of art. The question is—what's next? What will art be like, in a world where our core task is not only to question an outdated order of things, but to create a whole new one?</p> <p>By placing it between an insight that demands that new forms of expression be created, and another one that demands new societal structures, this conversation offers to art a vast new frontier.</p> <p>Debord's Society of the Spectacle can here be federated.</p>