CONVERSATIONS

Contents

Federation through Conversations

The paradigm strategy

Large change made easy

Donella Meadows talked about systemic leverage points as those places within a complex system "where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything". She identified "the mindset or paradigm out of which the goals, rules, feedback structure arise" as the most impactful kind of systemic leverage points. She identified specifically working with the "power to transcend paradigms" – i.e. with the very fundamental assumptions and ways of being out of which paradigms emerge – as the most impactful way to intervene into systems.

We are proposing to approach and handle our contemporary condition in this most powerful way.

If you've really taken the time to digest what's been said in Federation through Images and Federation through Stories, then you'll have no difficulty understanding why we've remained stuck in a paradigm – even when both our knowledge and our situation is calling for such change: It is no longer possible to make a convincing argument that a some given worldview – any worldview – represents the reality as it truly is!

Evolving beyond the paradigms

Have you noticed how different cultures have tenaciously held on to their worldviews or paradigms as the only right ones? Even to the extent of waging wars on people who upheld a different variant of the same religion – in which killing was forbidden by divine command!

It has now – by virtue of what we've just said above – become possible to do something incomparably more germane to creative changes of our condition, and to enhancing our evolution. And that is to transcend paradigms (as they have been traditionally) altogether; to liberate ourselves from any fixed way of conceiving of reality – and to enable new forms of awareness to emerge responsibly yet freely.

It is to ignite this way of evolving that is the core purpose of our conversations.

These conversations are dialogs

Changing the world by changing the way we communicate

There is a way of listening and speaking that fits our purpose quite snuggly. Physicist David Bohm called it the dialogue, and we'll build further on his ideas and the ideas of others, and weave them into the meaning of another one of our keywords, the dialog.

Bohm considered the dialogue to be necessary for resolving our contemporary entanglement. Here is how he described it.

I give a meaning to the word 'dialogue' that is somewhat different from what is commonly used. The derivations of words often help to suggest a deeper meaning. 'Dialogue' comes from the Greek word dialogos. Logos means 'the word' or in our case we would think of the 'meaning of the word'. And dia means 'through' - it doesn't mean two. A dialogue can be among any number of people, not just two. Even one person can have a sense of dialogue within himself, if the spirit of the dialogue is present. The picture of image that this derivation suggests is of a stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us. This will make possible a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which will emerge some new understanding. It's something new, which may not have been in the starting point at all. It's something creative. And this shared meaning is the 'glue' or 'cement' that holds people and societies together.

Contrast this with the word 'discussion', which has the same root as 'percussion' an 'concussion'. It really means to break things up. It emphasises the idea of analysis, where there may be many points of view. Discussion is almost like a Ping-Pong game, where people are batting the ideas back and forth and the object of the game is to win or to get points for yourself. Possibly you will take up somebody else's ideas to back up your own - you may agree with some and disagree with others- but the basic point is to win the game. That's very frequently the case in a discussion.

In a dialogue, however, nobody is trying to win. Everybody wins if anybody wins. There is a different sort of spirit to it. In a dialogue, there is no attempt to gain points, or to make your particular view prevail. Rather, whenever any mistake is discovered on the part of anybody, everybody gains. It's a situation called win-win, in which we are not playing a game against each other but with each other. In a dialogue, everybody wins.

We are not just talking

Don't be deceived by this word, "conversations". These conversations are where the real action begins.

By developing these dialogs, we want to develop a way for us to bring the themes that matter into the focus of the public eye. We also want to bring in the giants and their insights, to help us energize and illuminate those themes. And then we also want to engage us all to collaborate on co-creating a shared understanding that reflects the best of our joint knowledge and insight.

And above all – we want to create a way of conversing that works; which makes us "collectively intelligent". We want to evolve in practice, with the help of new media and real-life, artistic situation design, a public sphere where the events and the sensations will be the ones that truly matter – i.e. the ones that are the steps in our advancement toward a new cultural and social order.

In a truest sense, the medium here really is the message!

Conversations that matter

Imagine now, if you have not done that already, that you are facing this task – of choosing just a handful of themes that matter; the ones that will be most suitable for us to initiate this process. What themes would you choose? We have tentatively chosen three themes, to begin with. In what follows we'll say a few words about each of them.

The Paradigm Strategy dialog

How to respond to contemporary condition

The theme we chose for The Paradigm Strategy dialog appeared to us as perhaps the most natural one, which had to be represented in this showcase of knowledge work that illuminates the way: How to respond to contemporary issues.

We wrote the following in the abstract where this idea was initially shared

The motivation is to allow for the kind of difference that is suggested by the comparison of everyone carrying buckets of water from their own basements, with everyone teaming up and building a dam to regulate the flow of the river that is causing the flooding. We offer what we are calling The Paradigm Strategy as a way to make a similar difference in impact, with respect to the common efforts focusing on specific problems or issues. The Paradigm Strategy is to focus our efforts on instigating a sweeping and fundamental cultural and social paradigm change – instead of trying to solve problems, or discuss, understand and resolve issues.

A roadmap for guided evolution of society

At the same time this dialog introduces a roadmap for guided evolution of society – and it develops further by engaging and weaving together our collective knowledge and ingenuity. Can we perceive our own time, our own blind spots and evolutionary entanglements, in a similar way as we now see the dark side of the Middle Ages?

This too is a natural theme – because what could be a better way to showcase the new approach to knowledge, than by providing what's been lacking – as Neil Postman insightfully observed:

The problem now is not to get information to people, but how to get some meaning of what's happening.(...) Even the great story of inductive science has lost a good deal of its meaning, because it does not address several questions that all great narratives must address: Where we come from; what's going to happen to us; where we are going, that is; and what we're supposed to do when we are here. Science couldn't answer that; and technology doesn't.

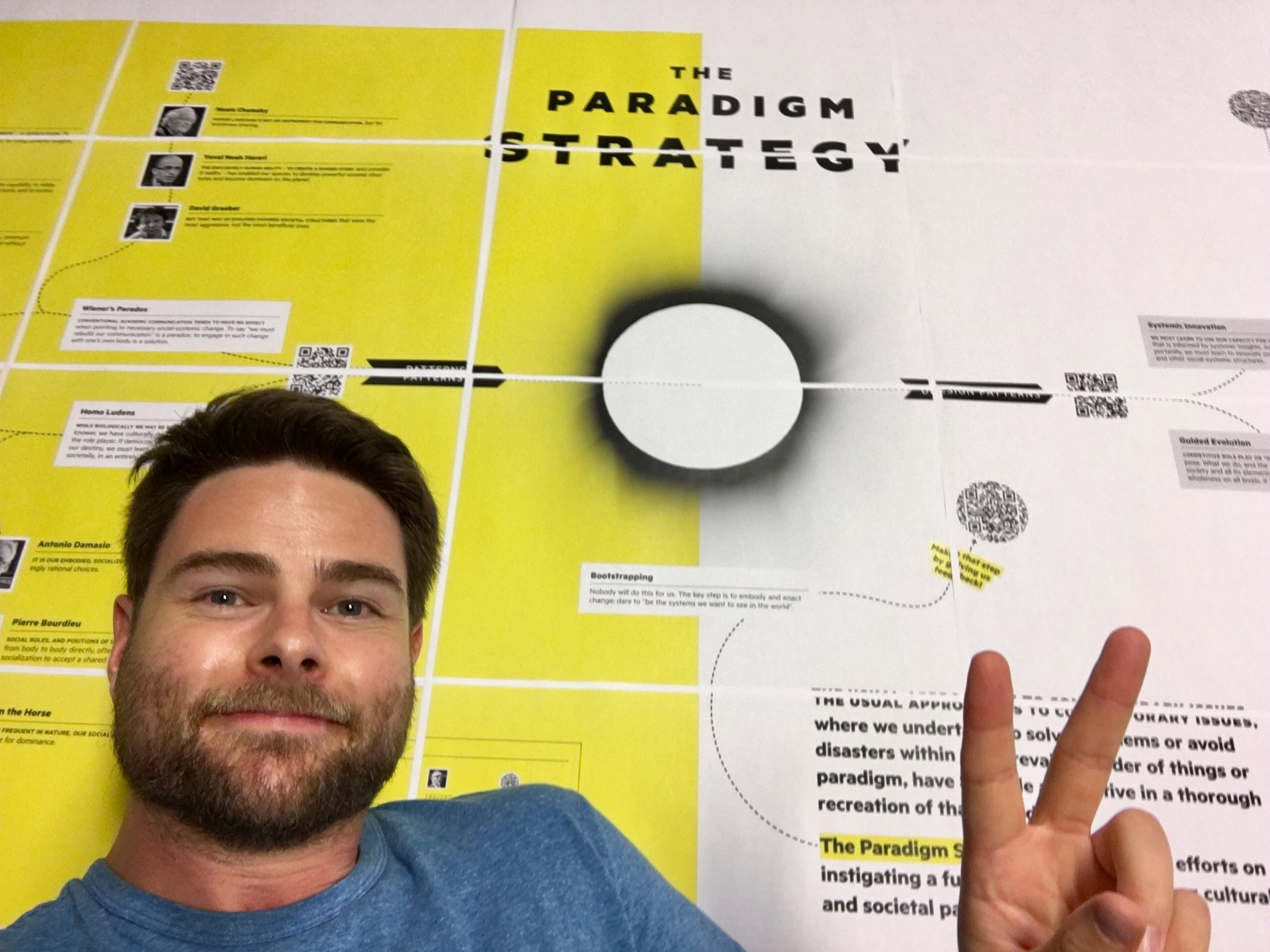

The Paradigm Strategy poster

How can we combine together the core insights of giants in in the humanities – and use them to illuminate our way into the future?

We created an interactive multimedia document that combines a variety of techniques including vignettes, threads, patterns, gestalt and prototypes – as a way to organize and orient a situated intervention and a physical and an online dialog.

It will be best if you open and look at The Paradigm Strategy poster as we speak.

What you see in the middle is what we generally call gestalt, and in this specific case the Key Point – it's the pivotal point of change, the wormhole from this paradigm into its transformation. On the left we show where we come from – by weaving together the stories or vignettes of giants into threads and threads into patterns. On the right we show where we are going – or should be going, by illustrating the emerging paradigm by a handful of prototypes. There is also a specific advice how to move from the present condition to the next, how exactly to go into and through the point in the middle, or "what we're supposed to do when we are here" – which we called "bootstrapping".

You'll notice that there are 12 vignettes; they do not attempt to complete the roadmap, or fully explain "where we come from" (you'll notice that most of what's been told on these pages is not represented). They, however, should be sufficient to reach the main insight.

There's a good reason why we use those vignettes: They bring abstract and high-level insights down to earth, make ideas palpable, and real. We cannot possibly do this in this very brief summary! And yet by only speaking abstractly we would risk completely missing our main point – which is to gently guide our audiences to the metaphorical mountain top, from where the naked realness of what we are talking about is seen with clarity and precision.

So what we'll do here is a compromise: We'll just sketch a single vignette in some detail; and give only a gesture drawing of all the rest.

How Pierre Bourdieu become a sociologist

As the Chair of Sociology at the Collège de France, Pierre Bourdieu was at the very peak of his profession, in effect representing the science of sociology to the French people. The story we'll tell is about an insight that got him there. Just like Doug Engelbart, and like many of the giants, Bourdieu was moved to do what he did by first having an insight; by observing something that could make a difference that makes a difference.

At the beginning of our story Bourdieu is an army recruit in annexed Algeria, where a civil war is raging. And he has no difficulty noticing how the official narrative (that France was in Algeria to bring economic progress and culture) collapsed under the weight of evident tortures and murders and abuses of all kinds – and seeing the naked and ugly real face of contemporary imperialism. So he decided to write a small booklet about this in an accessible language, in the Que sais-je edition (which you may think of as a bit more serious variant of the familiar book series "For Dummies").

Back home in France this booklet contributed to politicization of French intelligentsia during the 1950s and 60s. But in Algeria it had another effect. A contact would bring Bourdieu to an "informant" (for example a man who'd been tortured) and say "You can trust this man – completely!" What a magnificent way for a brilliant young man to look into the nuts and bolts of a human society, at the point where it is buoyantly transforming!

It was not only the war that was played on this historical stage. The war would soon be over, and the Algerian society would begin a whole new phase – of "modernization".

With palpable sympathy and affection, Bourdieu was 'a fly on the wall' in a Kabyle village household, recording the beautifully-intricate harmony that existed between the organization of the house and the relationships among its people. It was then not difficult for Bourdieu to notice how painfully this harmony collapses when the Kabyle young man is forced, by new economic necessities, to look for employment in the city. Not only his sense of honor, but even his very way of walking and talking was out of sync. And even to the young women from the same village – who'd seen something entirely different in movies and in restaurants.

In this way Bourdieu got to realize that the old relationships of economic and cultural domination did not at all vanish – they only changed their manner of expression!

All this made Bourdieu remember – and understand – what he himself had been experiencing after having moved from Denguin (an alpine village in Southern France) to join the chosen ones in French academia by studying in the uniquely prestigious Parisian École normale supérieure (not by birthright but owing to his exceptional talents) – what difference it made to know the right brands, and wines, and have the right table manners and the right manner of speech.

The theory of practice

The theory that resulted Bourdieu aptly called "theory of practice" – it being a theory of how the society evolves and operates in practical reality.

The keywords "symbolic power", "habitus" and "field" will suffice for us to represent it here. Let's just say that the power – which was once seen to be manifested in prisons and chains and torture chambers – can functions quite well without all that, through only symbolic means; and that this "symbolic power" works without the awareness of its existence on any side – neither of its winners or losers, victors or victims. Just the embodied manners of the "habitus", and the subtle coercion of the "field" turns out to be enough.

But before we revisit those concepts, let's just briefly sketch the other two vignettes in the same thread – which will help us see Bourdieu's theory in even a bit different light than what he may have intended.

Odin the horse

Odin the Horse is a brief real-life story about the territorial behavior of Icelandic horses. But it's also a bit of a private joke, whose explanation we shall see a bit later. The point made (we are rushing ahead – but we can develop these points later, in a conversation) is that we could be engaging in (...)

Can we use knowledge federation to turn even a profane theme as "evolution" into a sensation? (We are of course talking about our cultural and societal evolution, the evolution that matters.)

While we let ourselves be guided by our natural wish to save your time and attention, by showing you a crisp and clear picture of the elephant on a very high level that is, without too much detail – we risk missing the real point of our undertaking, which is to give an exciting, palpable, moving, spectacular, breath-taking... vision or "narrative". You might remember the vignettes we introduced in Federation through Stories? The point is to present abstract ideas through stories, which give them realness and meaning. And (you'll also remember) each of these stories, in a fractal-like or parable-like way, portrays the whole big thing. So let us here slow down a moment and introduce just one single giant through his story. Not because his story is the most interesting of them all – but because it alone points to what might be the very heart of our matter, that is, of the emerging paradigm or the elephant. And even so – all we'll be able to do is provide some sketches, and rough contours, but please bear with us – we are only priming this conversation. As we begin to speak, the details will begin to shine through, and so will the elephant.

So let's follow Bourdieu from his childhood in Denguin (an alpine village in Southern France) to his graduation in philosophy from the uniquely prestigious Parisian École normale supérieure (where just a handful of exceptionally talented youngsters are given the best available support to raise to the very top of a field). A refusal to attend the similarly prestigious military academy (which was the prerogative of the ENS graduates) led Bourdieu to have his military service in Algeria, which is where the real story begins.

Upon return to France Bourdieu would ultimately raise to the very top of sociology (he occupied the Chair of Sociology at the Collège de France) – largely by developing the insights he acquired back in Algeria. notice that Bourdieu was not educated as a sociologist – he became one by observing how the society really operates, and evolves. And by turning that into a theory, which he aptly called "Theory of Practice". What did he see?

Two things, really. First of all he saw the ugly and brutal side of French imperialism manifest itself (as torture and all imaginable other abuses) during the Algerian War in 1958-1962. Bourdieu wrote a popular book about this, in French Que sais-je series, which very roughly corresponds to Anglo-American "For Dummies". In France this book contributed to the disillusionment with the "official narrative". And in Algeria it made him trusted (someone would take him to an 'informant', perhaps a one who has been tortured, and say "you can trust this man completely") – and hence privy of the kind of information that few people could access.

This led to the second and main of Bourdieu's observations – of the transformation of the rural Kabyle society with the advancement of modernization. It is with great pleasure and admiration that one reads Bourdieu's writings about the Kabyle house and household, with its ethos and sense of duty and honor arranging both the relationships among the people and their relationships with things within and outside their dwellings. And yet – Bourdieu observed – when a Kabyle man goes to town in search of work, his entire way of being suddenly becomes dysfunctional. Even to the young women of his own background – who saw something entirely different in the movies and in the cafes – the way he walks and talks, and of course his sense of honor... became out of place. The insight – which interests us above all – is that the kind of domination that was once attempted, unsuccessfully, through military conquest – became in effect achieved not only peacefully, but even without anyone's awareness of what was going on. The symbolic power – as Bourdieu called it – can only be exercised without anyone's awareness of its existence!

To compose his Theory of Practice, Bourdieu polished up certain concepts such as habitus (which was used already by Aristotle and was brought into sociology by Max Weber), and created others, such as "symbolic capital" and "field" which he also called "game". A certain subtly authoritative way of speaking may be the habitus of a boss. The knowledge of brands and wines, and a certain way of holding the knife and fork may be one's social capital – properly called a "capital" because it affords distinct advantages and is worth "investing into", because it gives "dividends". But let's explain the overall meaning of this theory of practice and its relevance, by bringing it completely down to earth and applying it to some quite ordinary social "practice" – which marked our social life throughout history.