Difference between revisions of "A small practical example"

m |

m |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | <div class="page-header" > <h1>An intuitive introduction to systemic thinking</h1> </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Attention as resource</h2></div> |

| − | <div class="col-md-7"><h3> | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>What a giant had to say</h3> |

| − | <p>Think of the attention of our children as a resource | + | <p>Many years ago, when the teachers still had time to listen to [[giants|<em>giants</em>]], and when they still had control over our children's education, here is what [[William James]] had to tell them about the subject of attention. |

| − | <p>But our industries have managed to separate this emotion | + | <blockquote> |

| + | Text | ||

| + | </blockquote></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

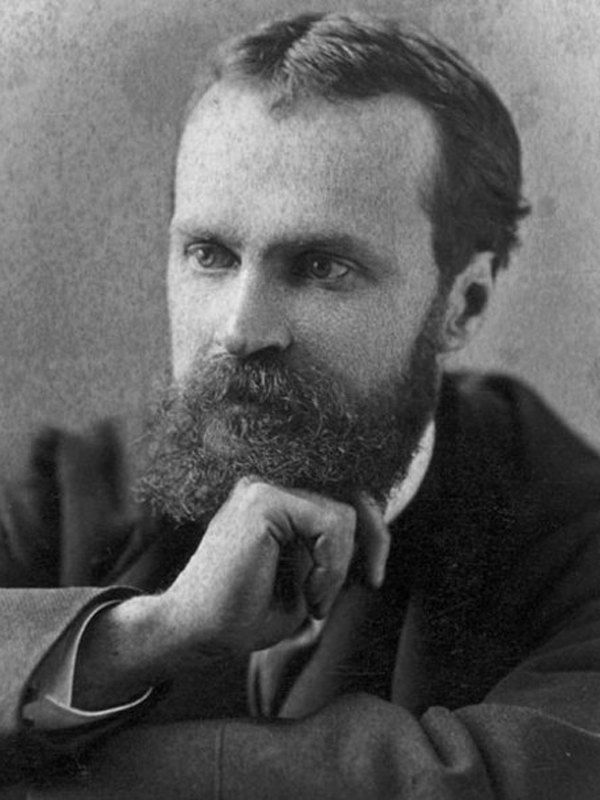

| + | <div class="col-md-3 round-images"> [[File:James.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[William James]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <h3>What we ended up doing</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Think of the attention of our children as a resource. And of interest as the emotion by which the use of this resource is naturally guided. It is this emotion that may naturally guide our young ones to explore the world they live in. It is what the world traditions used to deliver ethical messages, by weaving them into interesting fables. It is what might compel our youngsters to train the body and the character, by doing sports.</p> | ||

| + | <p>But our industries have managed to separate this emotion from the contexts where it may be useful. They have created games that train only our kids' two thumbs and rear ends – and whose other effects may be just negative. </p> | ||

<h3>Naive pursuit of happiness</h3> | <h3>Naive pursuit of happiness</h3> | ||

| − | <p>Of course we | + | <p>This is of course just an instance of a more general trend – of the way in which our "pursuit of happiness" has developed. Of course we mean no harm to our little darlings. We only want them to be happy! And if we've mistaken happiness for that flimsy emotion – that something <em>feels</em> attractive or pleasant at the moment – isn't that what we've done also to ourselves?</p> |

| − | < | + | <h3>Naive use of attention</h3> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>When we say "naive", we really mean uninformed or <em>mis</em>-informed.</p> |

| − | <p>We say "for all we know", because | + | <p><em>For all we know</em>, we may have created a complex and dangerous world, and brought our children into this world, without seriously considering what they might need to answer to its demands. Can you imagine anything so (potentially) cruel?</p> |

| − | <p>The | + | <p>We say "for all we know", because we <em>don't</em> really know. This possibility is somehow there, and yet it's not really there, because it's not been part of our concerns.</p> |

| − | <p>Our friends who innovate in journalism told us that there's just about one single business model that's left to journalists, as the way to compete with abundant free information. They call it "attention economy", but it's not what you might think | + | <p>The reason is that we've also treated <em>our own attention</em> as we have treated theirs.</p> |

| + | <p>Our friends who innovate in journalism told us that there's just about one single business model that's left to journalists, as the way to compete with abundant free information. They call it "attention economy", but it's not what you might think – that they are economizing with our attention as a resource, and allocating it as it's most needed. The meaning of "attention economy" is indeed <em>opposite</em> from that – it means attracting our attention by whatever means might be available, and selling it (as a commodity, measured by the numbers) to advertisers.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>Naive use of information</h3> | ||

<p>But journalism, or public informing, it's those very 'headlights' of the metaphorical 'bus'. It's what shows the world to most of us, it's what is supposed to orient us and inform our action. What we have, however, is the traditional format – just showing events happening around the world – (which we may still associate with the idea of "good" journalistm) – and which all too often disintegrates into just attention grabbing by showing anything that may still grab attention.</p> | <p>But journalism, or public informing, it's those very 'headlights' of the metaphorical 'bus'. It's what shows the world to most of us, it's what is supposed to orient us and inform our action. What we have, however, is the traditional format – just showing events happening around the world – (which we may still associate with the idea of "good" journalistm) – and which all too often disintegrates into just attention grabbing by showing anything that may still grab attention.</p> | ||

<p>(We may observe in passing that even in the most reputable media the front-page attention tends to be given to a most recent sensational action of some politician, such as Donald Trump, or of some group of militant fundamentalists. The question is whether our attention is due there? We may also observe that while the commentary may be critical, in the <em>systemic</em> sense the acts of those politicians and terrorists may still be in synergy with the system of our public informing as it is today. But let's not go down <em>that</em> rabbit hole either, not at the moment...)</p> | <p>(We may observe in passing that even in the most reputable media the front-page attention tends to be given to a most recent sensational action of some politician, such as Donald Trump, or of some group of militant fundamentalists. The question is whether our attention is due there? We may also observe that while the commentary may be critical, in the <em>systemic</em> sense the acts of those politicians and terrorists may still be in synergy with the system of our public informing as it is today. But let's not go down <em>that</em> rabbit hole either, not at the moment...)</p> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 37: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | ---- | + | ----- |

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>A tiny example</h2></div> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>A | ||

<div class="col-md-7"><h3>The definition of addiction</h3> | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>The definition of addiction</h3> | ||

<p>Now here's an example you probably won't even notice, if you just read Federation through Applications. It's at the very end, and – yes – drowning in an ocean... of ideas. But let's pull it out, for illustration, and see what it has to say. (It's of course one out of very many such things; understanding the paradigm means seeing the relationships. This will just illustrate how this all works.)</p> | <p>Now here's an example you probably won't even notice, if you just read Federation through Applications. It's at the very end, and – yes – drowning in an ocean... of ideas. But let's pull it out, for illustration, and see what it has to say. (It's of course one out of very many such things; understanding the paradigm means seeing the relationships. This will just illustrate how this all works.)</p> | ||

<p>Lots and lots of new addictions? ...</p> | <p>Lots and lots of new addictions? ...</p> | ||

<p>Definition as [[patterns|<em>pattern</em>]] – makes all the difference...</p> | <p>Definition as [[patterns|<em>pattern</em>]] – makes all the difference...</p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | ----- | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Occupy your profession</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>Occupy your university</h3> | ||

| + | <p>But we are already there – there's nothing to occupy! Really just stop and think!</p> | ||

</div></div> | </div></div> | ||

Latest revision as of 10:52, 8 October 2018

An intuitive introduction to systemic thinking

Attention as resource

What a giant had to say

Many years ago, when the teachers still had time to listen to giants, and when they still had control over our children's education, here is what William James had to tell them about the subject of attention.

Text

What we ended up doing

Think of the attention of our children as a resource. And of interest as the emotion by which the use of this resource is naturally guided. It is this emotion that may naturally guide our young ones to explore the world they live in. It is what the world traditions used to deliver ethical messages, by weaving them into interesting fables. It is what might compel our youngsters to train the body and the character, by doing sports.

But our industries have managed to separate this emotion from the contexts where it may be useful. They have created games that train only our kids' two thumbs and rear ends – and whose other effects may be just negative.

Naive pursuit of happiness

This is of course just an instance of a more general trend – of the way in which our "pursuit of happiness" has developed. Of course we mean no harm to our little darlings. We only want them to be happy! And if we've mistaken happiness for that flimsy emotion – that something feels attractive or pleasant at the moment – isn't that what we've done also to ourselves?

Naive use of attention

When we say "naive", we really mean uninformed or mis-informed.

For all we know, we may have created a complex and dangerous world, and brought our children into this world, without seriously considering what they might need to answer to its demands. Can you imagine anything so (potentially) cruel?

We say "for all we know", because we don't really know. This possibility is somehow there, and yet it's not really there, because it's not been part of our concerns.

The reason is that we've also treated our own attention as we have treated theirs.

Our friends who innovate in journalism told us that there's just about one single business model that's left to journalists, as the way to compete with abundant free information. They call it "attention economy", but it's not what you might think – that they are economizing with our attention as a resource, and allocating it as it's most needed. The meaning of "attention economy" is indeed opposite from that – it means attracting our attention by whatever means might be available, and selling it (as a commodity, measured by the numbers) to advertisers.

Naive use of information

But journalism, or public informing, it's those very 'headlights' of the metaphorical 'bus'. It's what shows the world to most of us, it's what is supposed to orient us and inform our action. What we have, however, is the traditional format – just showing events happening around the world – (which we may still associate with the idea of "good" journalistm) – and which all too often disintegrates into just attention grabbing by showing anything that may still grab attention.

(We may observe in passing that even in the most reputable media the front-page attention tends to be given to a most recent sensational action of some politician, such as Donald Trump, or of some group of militant fundamentalists. The question is whether our attention is due there? We may also observe that while the commentary may be critical, in the systemic sense the acts of those politicians and terrorists may still be in synergy with the system of our public informing as it is today. But let's not go down that rabbit hole either, not at the moment...)

The advertising, on the other hand, is ubiquitous. Even great Google earns on it 90% of its revenue. It may seem that we are getting lots of things for free. But systemically – we have sold our very culture, that is, the basic mechanisms by which it is created, along with the underlying values. What's the real price we have paid?

You cannot blame the journalists, or the advertising agencies. They too are just "doing their job", just trying to survive, in a world where knowledge is not federated (so that they may have better things to tell to people), and where they are just struggling to survive by being fit, as fitness is defined by the ecology of their professions or systems.

But in all this mess, in all this systemic madness, there's this one thing we've done right: We have created a large resource, virtually a large global army of people, selected, trained and publicly sponsored – and by the magic of academic tenure, which still exists in some parts of the world, given the freedom to think and do freely, as they think might best serve the public that is sponsoring us. (We are saying "us", because although our work has largely been sponsored by the enthusiasm and the sacrifices of its members, it would have clearly been impossible without at least some of us having academic tenure. And anyhow, knowledge federation as it is today, is an academic prototype.)

How are we using this most valuable resource?

Well the answer is well known and obvious. To be an academic researcher in good standing, you must either be in the maths or physics or philosophy... You must belong to one of the traditional disciplines, and pursue the disciplinary interests. You must either publish, or perish.

(We note in passing that Douglas Engelbart, the knowledge federation's icon giant, left the U.C. Berkeley, where he initially thought he could pursue his vision, when an elder colleague told him that unless he stops dreaming and starts publishing peer-reviewed articles, he would remain an adjunct assistant professor forever. This story Doug did manage to tell at his 2007 presentation at Google. The details of this story, in the context of which this comment will make sense, are told in Federation through Stories.)

Well you can't blame our academic colleagues either. We too are just trying to survive in the competitive world – where to be successful, we are simply compelled to rush and be busy, where we don't have the luxury to stop and think... for example about the meaning and purpose of it all.

A tiny example

The definition of addiction

Now here's an example you probably won't even notice, if you just read Federation through Applications. It's at the very end, and – yes – drowning in an ocean... of ideas. But let's pull it out, for illustration, and see what it has to say. (It's of course one out of very many such things; understanding the paradigm means seeing the relationships. This will just illustrate how this all works.)

Lots and lots of new addictions? ...

Definition as pattern – makes all the difference...

Occupy your profession

Occupy your university

But we are already there – there's nothing to occupy! Really just stop and think!