STORIES

Contents

Federation through Stories

Modern physics had a gift for humanity

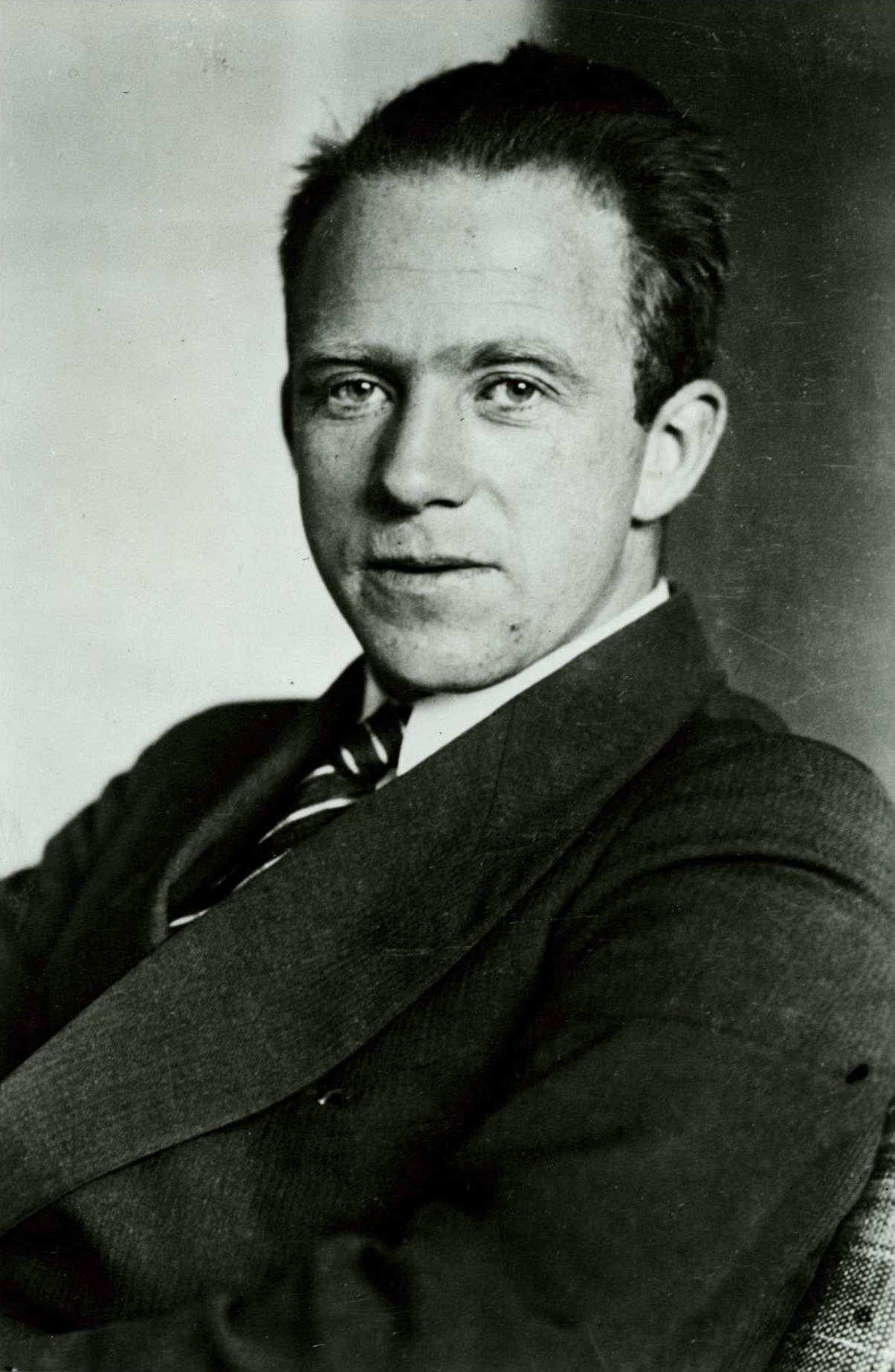

Werner Heisenberg got his Nobel Prize in 1932, "for the creation of quantum mechanics" which he did while still in his twenties. As a mature scientist, he realized that modern physics had a gift for humanity that was well beyond physics or even science at large, which had not yet been recognized. So in 1958 he published the monograph "Physics and Philosophy" (subtitled "the revolution in modern science") to correct that.

In this manuscript, Heisenberg explained how

the nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people.

He then pointed out how this frame of concepts was too narrow and too rigid for expressing some of the core elements of human culture – which as a result appeared to modern people as irrelevant. And how correspondingly limited and utilitarian values and worldviews became prominent. Heisenberg then explained how modern physics disproved this "narrow frame"; and concluded that

one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century.

If we now (in the spirit of systemic innovation, and the emerging paradigm) consider that the social role of the university (as institution) is to provide good knowledge and viable standards for good knowledge – then we see that just this Heisenberg's insight alone gives us an obligation – which we've failed to respond to for sixty years.

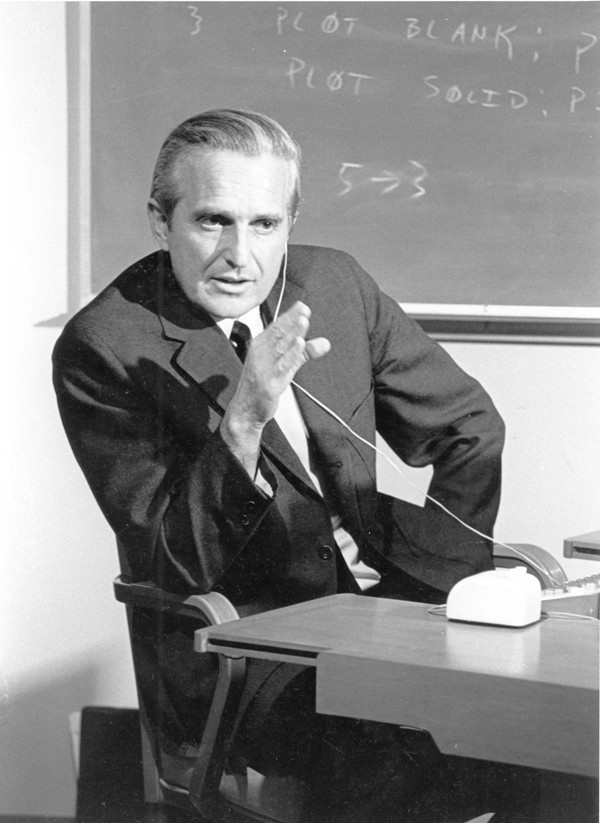

The incredible history of Doug

An epiphany

In December of 1950 Douglas Engelbart was a young engineer newly graduated from university, just engaged and freshly employed. He was looking at his career as a straight path to retirement. And he did not like what he saw.

Life should be more than that! So he made a decision – to direct his career so as to maximize its benefits to the mankind.

Facing now an interesting optimization problem, this idealistic young engineer spent three months thinking intensely how exactly to direct his efforts. Then he had an epiphany. The computer had just been invented. And the humanity had all those problems that were growing in complexity and urgency, which it didn't know how to solve. What if...

To begin to pursue his vision, Engelbart quit his job and enrolled at the doctoral program in computer science at U.C. Berkeley.

Silicon Valley's giant in residence

It took awhile for the people in Silicon Valley to realize that the core technologies were not developed by Steve Jobs and Bill Gates; nor at the XEROX Palo Alto Research Center where they took them from – but by Douglas Engelbart and his SRI-based research team. On December 9, 1998 a large conference was organized at Stanford University to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Engelbart's Demo, where the networked interactive digital media technology – the kind of thing that is in common use today – was first shown to the public. Engelbart received the highest honors including the Presidental award and the Turing prize (a computer science equivalent to Nobel Prize). Allen Kay (another Silicon Valley personal computing pioneer) remarked "What will the Silicon Valley do when they run out of Doug's ideas?".

And yet it was clear to Doug – and he also made it clear to others – that he felt celebrated for wrong reasons. The crux of his vision remained unfulfilled, and even ignored. Doug was notorious for telling people "You just don't get it!"

On July 2, 2013 Doug passed away, celebrated and honored – yet feeling he had failed.

The Silicon Valley failed to understand its giant in residence – even after having recognized him as that!

The 21 century printing press

What was it that the Silicon Valley developers, business leaders and academics "just didn't get"?

The printing press is a fitting metaphor for answering this question, in the context of our big picture story, because the printing press was to a large degree the technical invention that led to the Enlightenment, by making knowledge widely accessible. If we would now ask what technology might play a similar role in the next Enlightenment-like change, you would most probably answer "the Web or (if you are technical) "the network-interconnected interactive digital media". And your answer would be right.

But there's a catch!

While there can be no doubt that the printing press led to a revolution in knowledge work, this revolution was only a revolution in quantity. The printing press only made what the scribes were doing more efficient! To communicate, people still needed to write and publish books, and hope that the people who needed what's written in them would find them on a shelf.

The network-interconnected interactive digital media, however, is a disruptive technology of a completely new kind; it is not a broadcasting device, but in a truest sense a "nervous system" connecting people together.

There are two very different ways in which this technology can be developed and put to use.

One of them is the habitual way – to use it as we used the printing press, to just increase the efficiency of what the people were already doing, help them print and publish faster all those articles and books and letters and...? (In the language of our central metaphor, this would mean using the new electrical technology to re-implement the candle.)

To see the problem this way of using the new technology most naturally leads to, imagine that your own nervous system were used in this way; that all your sensory cells were using your nervous system to just broadcast data to your brain. Your sanity would surely suffer. Well that's what has happened with (to use one of Doug's favorite keywords) our collective intelligence.

Neil Postman would observe – in 1990, just before the Web:

The tie between information and action has been severed. ...It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it.

Engelbart's legacy

Digital technology could help make this a better world. But we've also got to change our way of thinking.

These two sentences were intended to frame Engelbart's message to the world – that was to be delivered at Google in 2007. </p>

If there is sill doubt that it was systemic thinking Doug had in mind, consider the following excerpt (from an interview Doug gave as a part of a Stanford University research project):

I remember reading about the people that would go in and lick malaria in an area, and then the population would grow so fast and the people didn't take care of the ecology, and so pretty soon they were starving again, because they not only couldn't feed themselves, but the soil was eroding so fast that the productivity of the land was going to go down. Sol it's a case that the side effects didn't produce what you thought the direct benefits would. I began to realize it's a very complex world. I began to realize it's a very complex world. (...) Someplace along there, I just had this flash that, hey, what that really says is that the complexity of a lot of the problems and the means for solving thyem are just getting to be too much. So the urgency goes up. So then I put it together that the product of these two factors, complexity and urgency, are the measure for human organizations or institutions. The complexity/urgency factor had transcended what humans can cope with. It suddenly flashed tthat if you could do something to improve human capability to deal with that, then you'd realy contribute something basic. That just resonated. Then it unfolded rapidly. I think it was just within an hour that I had the image of sitting at a big CRT screen with all kinds of symbols, new and different symbols, not restricted to our old ones. The computer could be manipulating, and you could be operating all kinds of things to drive the computer. The engineering was easy to do; you could harness any kind of a lever or knob, or buttons, or switches, you wanted to, and the computer could sense them, and do something with it.

To see the crux of Engelbart's intended contribution to humanity, reflect on the difference a functioning nervous system could make with respect to humanity's ability to deal with complexity and urgency. To see why "different thinking" alias systemic innovation is necessary to get us there, imagine yourself walking toward a wall. Imagine that your eyes see that, but they are trying to tell it to your brain by writing academic articles in some specialized field of knowledge.

What the humanity's new nervous system required was, of course, a completely new division, specialization and coordination of knowledge work – that would turn the physical nervous system into a well-functioning one. And this is the context in which Engelbart's various less known technical contributions need to be understood. All of them – the open hyperdocument system, the networked improvement community, the dynamic knowledge repository and numerous others – were intended to be, and can only be understood, as building blocks in a completely new approach to knowledge.

While Engelbart was celebrated as a genius technology developer, his contribution will only be properly recognized when we consider it as a revolutionary contribution to human knowledge – or in other words as in the proper sense of the word academic.

But alas – Engelbar was only making a pivotal contribution to humanity's handling of knowledge; and to humanity's future. Having thus failed to be part of any of the recognized academic disciplines, his contribution remained unrecognized.